My first big project my students engaged in during the 2013-14 school year was, at best, a mediocre experience and, at worst, a giant waste of valuable instructional time we'd never get back. I was at a new school and had a lot of goals I wanted to explore - further investing time into developing classroom culture, engaging students into taking more ownership in their learning instead of being passive recipients, pushing students deeper while meeting them where they were at - in short, developing my teaching identity in a context with a lot of autonomy. I had total teaching freedom.

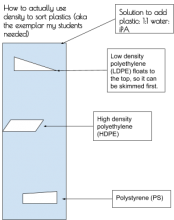

So, for the first unit on density, estimation and measurement, and classification of matter, I designed a project related to recycling plastics meant to drive the curriculum forward (remember, this isn’t something tacked on the end - student encountered the requirements of the task before knowing anything). The project was inspired by a lab I did in a polymer chemistry class 1 - how can shredded plastic be separated to be further processed (Density!)? Also, why should anyone believe your data for your method (Proper estimation! Use sig figs!)? Here are links to the entry document, supporting information 1, and supporting information 2 that were provided over the course of the experience.

For the first time ever, students experienced an entry event (and I facilitated one). They watched a video about the inner workings of a recycling plant, and then read a letter that asks for their help to separate a variety of plastics using solvents provided (water, isopropyl alcohol, etc). As a class, we completed knows, need to knows, and next steps and finally a problem statement. It had all the pieces of what I thought would make a successful project - relevant (I mean, it's Denver - we recycle here)! Multiple solutions to the problem! To separate the plastic, it required real understanding of the content! It was going to be awesome! (Notice all the superlatives).

Well, it went. After the entry event, students engaged in activities to learn about sig figs and density and went between learning activities for content and project work time. Here are some lessons I learned that first go around.

1. It's hard to solve a problem when you don't really understand the problem. I had my students make proposals of what they planned to do in the lab, and they had to be approved by me in order to move on. Sounds foolproof, right? I thought so too. I approved lab procedures that seemed legit - trying different solutions to test density. Then, once they were in the lab, they would separate their shredded plastic mixtures by hand, and then would test to see if the pre-sorted mixture would sink or float in a solvent system.

What?! They sorted by hand?!?!?! They saw that plastic floats in iPA and that is all they did?????????? UGH. Not exactly what I had in mind as a purposeful use of class time. That's when I realized that my students had no clue what was going on, and that they needed an exemplar (see below). This ended up being the ticket to help most of them really understand the problem a bit better. Why didn’t I do that earlier? I was worried that by showing an example, I'd take away some of the creativity - it wasn't really an authentic PBL experience. However, innovation in real life typically takes small incremental steps off of work done before. For instance, my Nokia brick phone was a precursor to the the iPhone; the horse and buggy came before the car. Who knew that a hastily drawn test tube on an index card (that I made pretty for you readers) would help my students make progress.

2. I understand the connections between learning experiences and project - do my students? Counting sig figs, density, and proper estimation of laboratory instruments - all of these skills and understandings were weaved in and out of the project. Did my students get it? Honestly, no. For instance, my students did a lab with golf balls and salt water to model density on a particulate level and adjust solvents to make the golf ball change its position in the glass, and students did a good job there. However, I never intentionally gave my students an experience to make that connection to their bigger task at hand (Did you read my #1 take away above?). Students often need help to make connections - because it takes practice, just like any other skill! I wonder what would have happened if we had just talked about it as a class for 5 minutes? Whiteboard some simpler models of their bigger task of sorting plastics? Anything?! Why didn’t I build this in?

3. To apply content to a big task, student should probably have a chance to practice it, fail at it, and adjust. This is so obvious, right? I was a fourth year teacher facilitating this project, and this is one of the more embarrassing revelations. My students couldn't apply their knowledge of sig figs because... they didn't have a chance to practice the basics. Yes, they had homework and exit tickets and such. But for these students, it wasn't enough and I was ignoring that because I was so freaked out by the length of the unit compared to previous years when there was not a project. Won’t they just pick it up during project work time? Maybe. It wasn’t here. When I realized this, I kind of back tracked to attempt to give this opportunity.

4. Review your problem statement every day. Really. Maybe even twice a day. I think back to my masters program and learning about teaching thinking I understood it - HA! Over and over again throughout my first years of teaching I'd think, "Oh, that's what they were getting at in that class." You don't know it until you know it. Well, it's the same with students. They don't really get the problem at hand until...they get the problem at hand. I had a teacher observe me and was kind of surprised by this remark "Is there a way to make sure all students know the purpose of the lab? I’m sure you’ve explained, but not everyone knows what concept they’re working on." Every student should be able to paraphrase that big problem statement independently. They may not know how to attack it quite yet, but things hopefully will click...but they have to internalize the bigger problem to do that. To internalize it, they have to know it.

5. Let go of things that get in the way of students making progress. Our internet was terrible at that time. I was stubborn - everything was online, I wanted students to use the class google docs to share what was going on in their group via knows, need to knows, and next steps. In fact, groups would obviously fail if their work wasn't transparent to other groups, right? Well, my pride nearly got the best of things. Halfway through the project, every group got a folder where I had printed out the stuff they'd typed up. They simply had more class time when I let go of my desire for transparency. No one had an excuse to not work.

6. This will take students a lot of time, because you should still be using the pedagogical skills you’ve already been using to guide student learning. You are not a horrible teacher for taking that time. This needed to be my mantra. I was so concerned about the amount of time we were spending on this that I cut things that I thought were fluff... like giving students enough practice on content. Like having a socratic seminar to make sure students understood a reading (that J Chem Ed paper I referenced earlier). You know, things that help students learn. That's the whole point of this, right? Ultimately, I had to do more spoon feeding (which wasted time, took away student opportunity to think deeply) in the back end because I didn’t actually practice good pedagogy that I would have used in any other situation (not related to a project).

Thanks for reading about some of my “duh” moments. If you are wondering how things are going now, I’d say better-ish. I have taken these lessons, and probably more that I can not even put to words, to keep trying. I never did try this recycling project again. Part of it is pride; part of it is that with the time commitment, there was really only time to do one of these big experiences per semester.

However, other projects I’ve developed I’ve done now 2-3 times each. Each time, students have gotten more and more out of the experiences as I think I have internalized all the moving parts that make these things work. I have evidence from their presentations and lab write ups. I’ve become comfortable with telling students “Huh, I...I mean the obviously real person from the community who needs you to complete this task… didn’t think of that… good question!” or “You know what - that was an oversight - let’s figure out how to get this to work for help you find information.” After a few years of, frankly, being too stupid to quit trying to give my students these types of experiences, my husband came in to be a project panelist (he’s an aerospace engineer...it was so great to have him there on a personal and professional level - he finally got to see why I worked so hard). That night, after eight hours of grading presentations, he said to me “Projects like these are key to developing real world job skills. Kids should be given every opportunity to keep developing these skills in conjunction with material learning (can you write the facts)...it’s not just enough to know the correct answer, but you must know how to communicate it. I didn’t get these chances until college…”

And that was when I knew that the years of struggle and practice has been worth it. Thanks for reading.

1 “Method for Separating or Identifying Plastics” Kolb, K.E.; Kolb, D.K. J. Chem. Ed. 1991.

All comments must abide by the ChemEd X Comment Policy, are subject to review, and may be edited. Please allow one business day for your comment to be posted, if it is accepted.

Comments 2

PBL can be so tricky at the beginning!

Thank you so much for sharing your experience. May I share you rblog post with teachers? I especially LOVE your last paragraph. Keep on keeping on, Tracy!

Thanks for reading!

Hi Kari-

Of course! I just ask that you attribute me/ChemEdX and provide a link to this post if you post this online. Feel free to also inclue my twitter handle as well! ([at]tracyhle).

Thanks!

Tracy