I teach an introductory college chemistry course for non-science majors called Chemistry of Everyday Things. Most of my students have little prior science experience, and they often begin the course intimidated by chemistry. I try to counter that science anxiety by letting my students choose the topics we focus on after a few weeks of fundamentals, and DNA has been a very popular choice each time. At first, I used the National Human Genome Research Institute’s protocol for extracting DNA from strawberries1, which they enjoyed, but I was not satisfied that they were connecting their fledgling understanding of chemistry to the hands-on work. Some students recalled from prior biology classes that A paired with T and C with G, and that DNA stored information, but they did not know why or how.

The activity I developed begins by having students examine the structures of the five traditional nucleobases found in DNA and RNA: adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), thymine (T), and uracil (U). Working in small groups, they compare the shapes of the molecules and consider what they know about polarity and intermolecular forces to choose at least one partner for each nucleobase. Then they explore a simple DNA model made of a long, folded strip of paper containing a double-stranded DNA sequence. By folding and unfolding the paper and recording the nucleobases that form complementary pairs, they model DNA replication and transcription. Using a set of cards labeled with tRNA anticodons and corresponding amino acids, they model RNA translation and produce a polypeptide with a short message hidden in its sequence of 1-letter amino acid symbols. It’s part exploration, part puzzle, and the students have a lot of fun with it.

I use this matching and modeling activity as part of a lab experiment that also includes the extraction of DNA from strawberries and a sheet of follow-up questions that students complete in their groups by the end of the lab period. The entire experiment, from pre-lab discussion to turning in the follow-up questions takes 2.5-3 hours. I estimate that the activity presented here takes less than 1 hour of class time.

Materials & Equipment

- Supplemental files (nucleobase cards, tRNA cards, DNA sequence strips)

- Computer with printer

- Cardstock (letter size; max. 3 sheets per group)

- Printer paper (letter size; ½ sheet per group + 2 sheets per student)

- Tape

- Paper cutter (recommended)

- Scissors

- Sandwich bags or small boxes (1 per group)

- Sharpened pencil with working eraser (1 per group)

- Notebooks, note sheets, or whiteboard for recording observations (recommended)

Instructor Preparation

Time required: 30-60 minutes the first time.

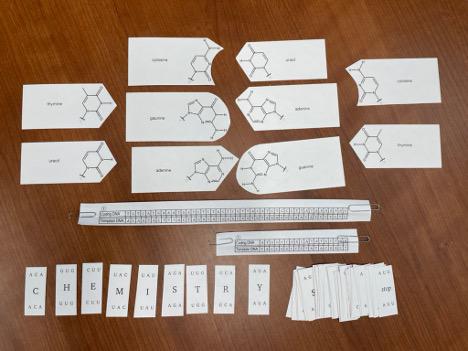

Print, cut, and assemble nucleobase cards, tRNA cards, and DNA sequence strips (found in the supplemental materials). Prepare an activity kit for each group: 10 nucleobase cards on cardstock, 64 tRNA cards on cardstock, 1 DNA sequence strip, and 1 pencil in a bag/box. If needed, two groups can share a single set of tRNA cards. Figure 1 shows the paper and cardstock pieces of the activity kit.

Nucleobase and tRNA cards can be reused. Subsequent preparation is 5-10 minutes to make new DNA sequence strips.

Figure 1: The components of the activity kit

Procedure

Time required: 1 hour

Split class into groups of 3-5 students.

Part I: Match Nucleobase Pairs

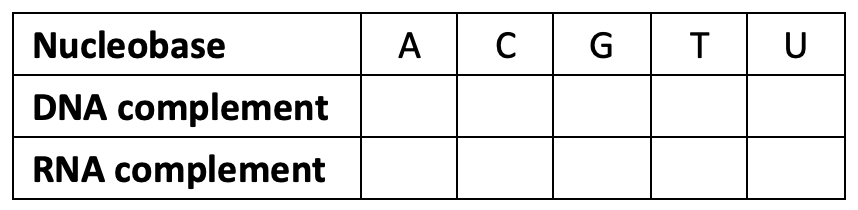

Each group of students examines the nucleobase structures on the provided cards and determines at least one pairing for each nucleobase (adenine, cytosine, guanine, thymine, uracil) based on the polarity and hydrogen bonding possibilities of each structure. They sketch the unique pairings, including hydrogen bonds for each pair. They use these pairings to fill in a table of complementary nucleobases (Table 1) that they will use in the parts that follow.

Table 1: Complementary nucleobases

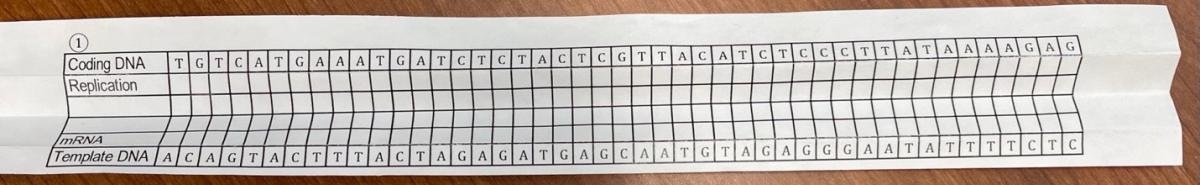

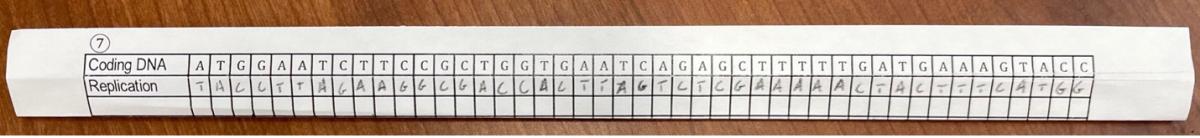

Part II: Model DNA Replication

The students check their group’s DNA sequence strip to make sure that the Coding DNA sequence has the correct complements in the Template DNA sequence. Then they “unzip” the DNA by unfolding the DNA sequence strip (Figure 2) and refold the strip so the Replication row is visible, and the mRNA and Template DNA rows are hidden (Figure 3). Using Table 1, they write the complement for each nucleobase in the Coding DNA in the Replication row. When they have finished, they can unfold the DNA sequence strip to compare their new Replication sequence with the Template DNA sequence. It is helpful to use pencil in case students decide to make corrections.

Figure 2: An “unzipped” DNA sequence strip

Figure 3: A refolded DNA sequence strip with the Replication row completed.

Part III: Model DNA Transcription

The students create a messenger RNA sequence using the Template DNA sequence, folding the Coding DNA and Replication rows back so they are hidden, and writing the RNA complement to the Template DNA on the mRNA row using Table 1. When they have finished, they can unfold the DNA sequence strip again to compare their mRNA sequence with the Coding DNA sequence, noting that RNA uses the nucleobase uracil, whereas DNA uses thymine.

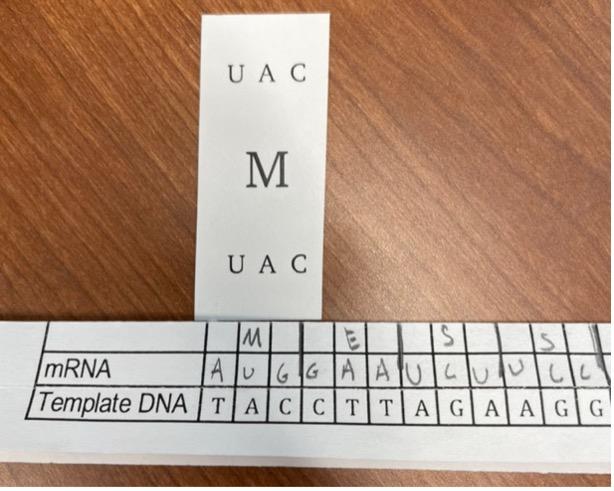

Part IV: Model RNA Translation

Each group of students uses the mRNA sequence from Part III and the tRNA cards to create an amino acid sequence. They divide the mRNA sequence into 3-base codons and search the tRNA cards for the complement sequence, referring to Table 1 as needed. They record the 1-letter symbol for the amino acid listed on each tRNA card, revealing a hidden message (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Matching a tRNA card to the mRNA sequence. The students have recorded the amino acid on the tRNA card (M) in the row above the mRNA sequence (AUG)

Variations & Extensions

The activity could be extended further to have students generate and encode their own short messages for other groups to decipher. They could work in reverse (amino acids to tRNA to mRNA to template to coding DNA) or use an inverse DNA codon table to skip from the amino acid symbols directly to the coding DNA strand.

For a more advanced group, or a course with a biochemical/biological focus, this simple paper model could be modified to include start codons and more of the transcription initiation process, emphasis on the direction of replication and Okazaki fragments, and more.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the Utica University students in Chemistry of Everyday Things (2023 and 2024) for their feedback about, and enthusiasm for, this activity in its prior iterations. I would also like to acknowledge Drs. Kelly Minerva and Nicole Lawrence of Utica University, whose “Start the Summer Off Write!” Academic Writing Retreat enabled me to write up this activity.

References

(1) How to extract DNA from a strawberry. National Human Genome Research Institute, 2023. https://www.genome.gov/about-genomics/teaching-tools/strawberry-dna-extr...