by Dean J. Campbell*

*Bradley University, Peoria, Illinois

Paper and Toy Models

A common method of analysis whether a molecule is polar or nonpolar is to consider the dipoles associated with each bond in the molecules as vectors of varying length and orientation, and then to add the vectors head-to-tail. If there is no net vector, the molecule is nonpolar; if there is a vector, the molecule is polar. In General Chemistry settings, students often struggle to visualize the dipole moments associated with some molecular structures. Molecular models are powerful visual aids for these sorts of analyses. The models themselves can vary in degrees of cost and sophistication. The models were built in this work from dedicated molecular model kits, toy building systems, and paper. The molecules modeled here were simple one- and two-carbon chlorinated hydrocarbons, since they can contain a variety of bond angles (e.g., 109.5°, 120°) and bond dipole directions (less electronegative hydrogen toward more electronegative carbon and less electronegative carbon toward more electronegative chlorine).

Models of Simple Chlorinated Hydrocarbons and Dipoles

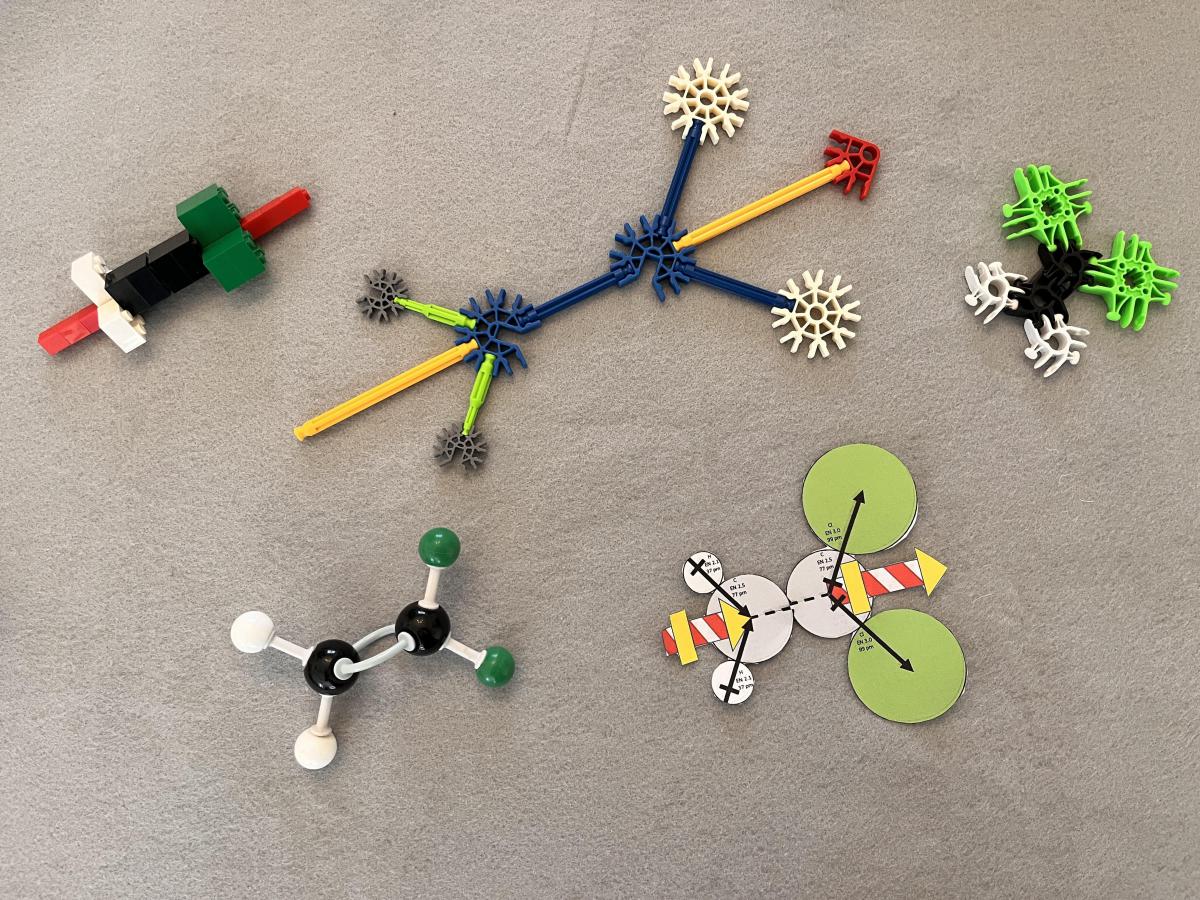

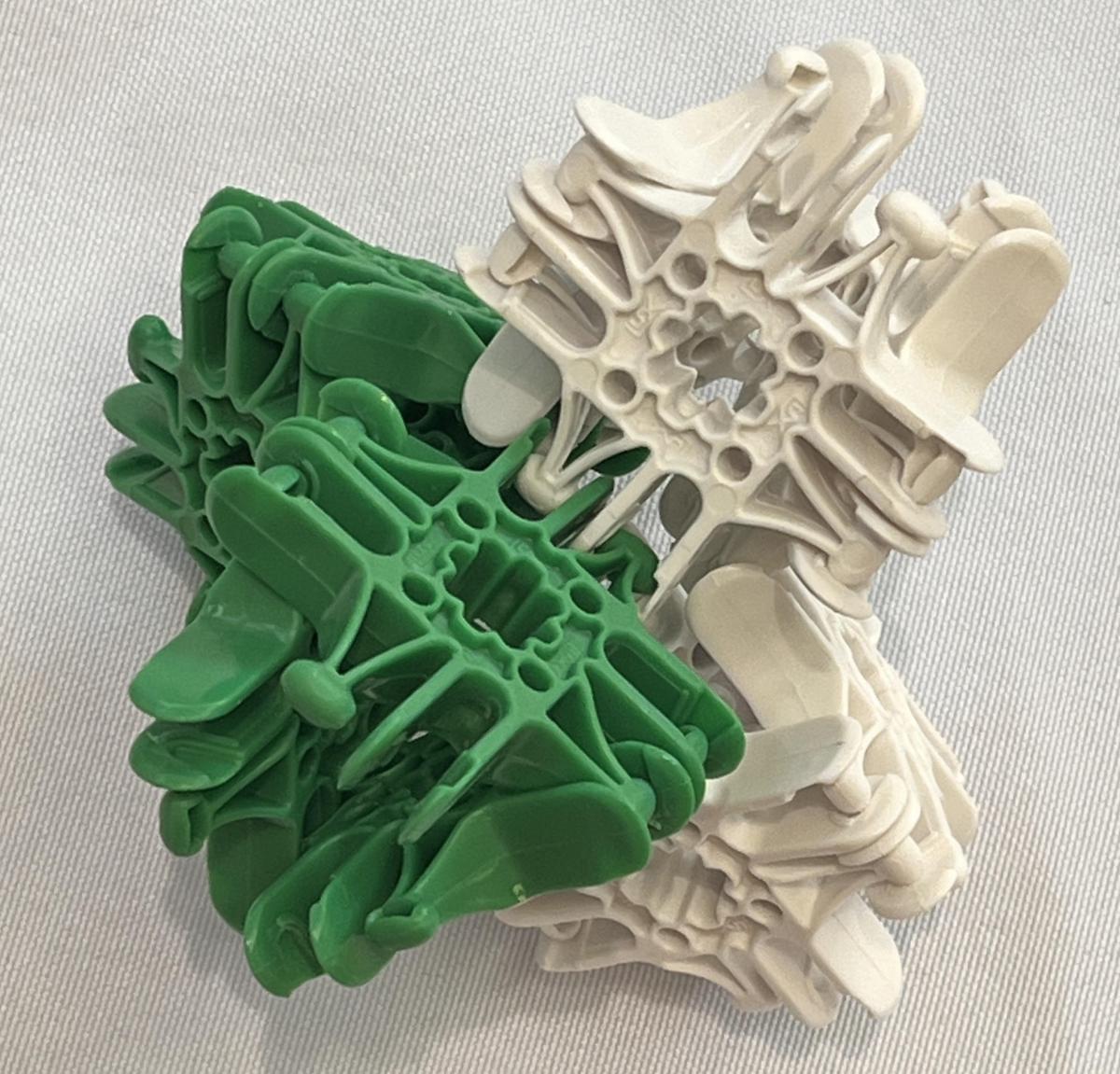

Chlorinated ethene compounds are planar, which have more easily analyzed dipole arrangements than chlorinated alkanes with more three-dimensional geometries. Figure 1 shows models of 1,1-dichlorothene made using LEGO, K’Nex, and Lux Blox building systems,1-3 as well as models made from a typical molecule building kit and paper. The central two objects in the models (bricks, circles, etc.) represent carbon atoms, and the outer objects represent hydrogen and chlorine atoms. The models are all oriented with the chlorine atoms at their right end in Figure 1. K’Nex, LEGO, and paper models also have representations of dipole vectors, all pointing toward the right toward the chlorine atoms. These are meant to be dipole vectors associated with each entire molecule. The dipole vectors bisect the angle formed by the carbon-hydrogen bonds and bisect the angle formed by the carbon-chlorine bonds.

Figure 1. Models of polar 1,1-dichloroethene: (TOP LEFT) LEGO bricks, including dipole vector representation, (TOP MIDDLE) K’Nex, including dipole vector representation, (TOP RIGHT) Lux Blox, (BOTTOM LEFT) molecular model kit, and (BOTTOM RIGHT) paper model including dipole vector representation.

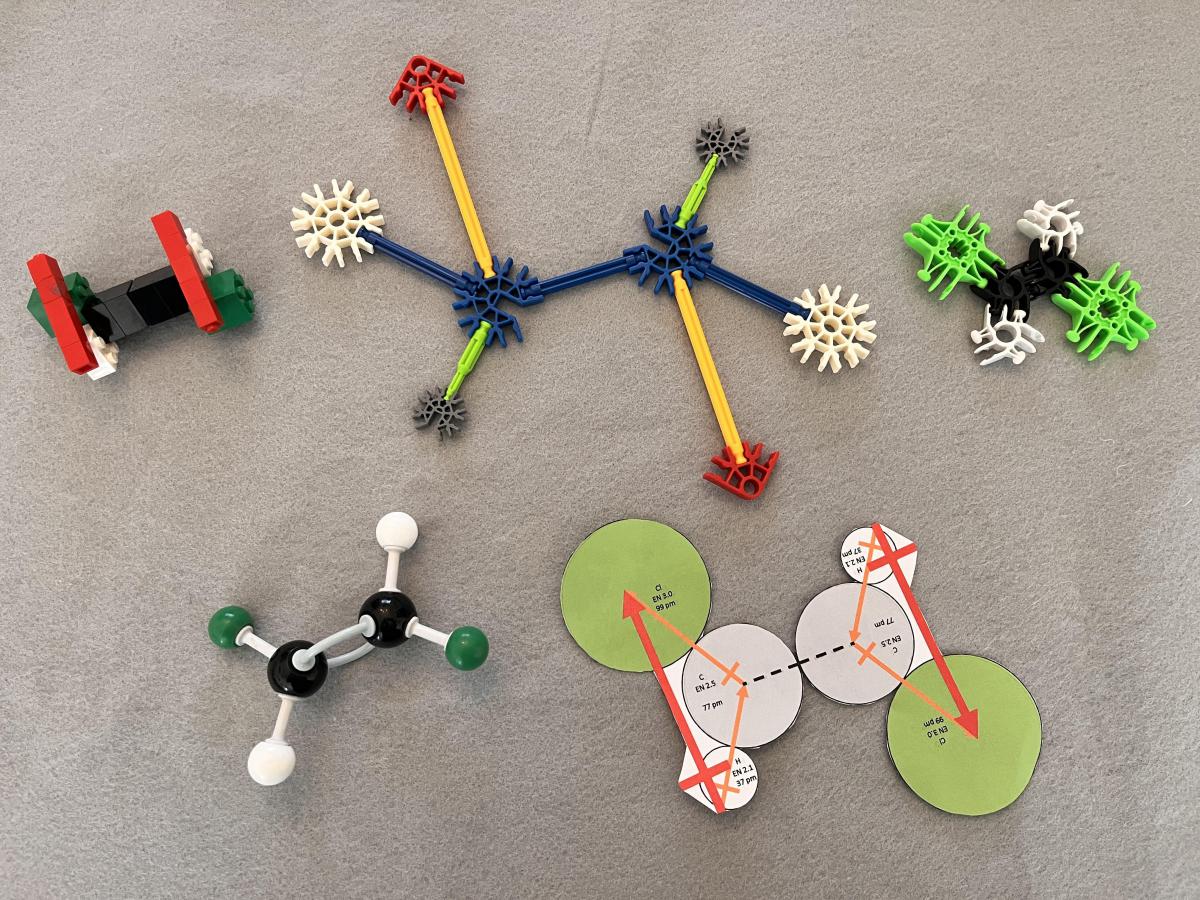

Figure 2 shows models of trans-1,2-dichlorothene made using LEGO, K’Nex, and Lux Blox building systems, as well as models made from a typical molecule building kit and paper. The LEGO, K’Nex, and paper models also have representations of dipole vectors for portions of the molecules. These vectors are a sum of a hydrogen-to-carbon dipole vector and a carbon-to-chlorine dipole vector for the three atoms making up half of each molecule. This approach simplifies four bond dipole vectors to two just dipole vectors for molecular polarity analysis. In the trans molecular geometry, these dipoles for the half-molecules point in opposite directions and cancel out to make nonpolar molecular models.

Figure 2. Models of nonpolar trans-1,2-dichloroethene: (TOP LEFT) LEGO bricks, including dipole vector representation, (TOP MIDDLE) K’Nex, including dipole vector representation, (TOP RIGHT) Lux Blox, (BOTTOM LEFT) molecular model kit, and (BOTTOM RIGHT) paper model including dipole vector representation.

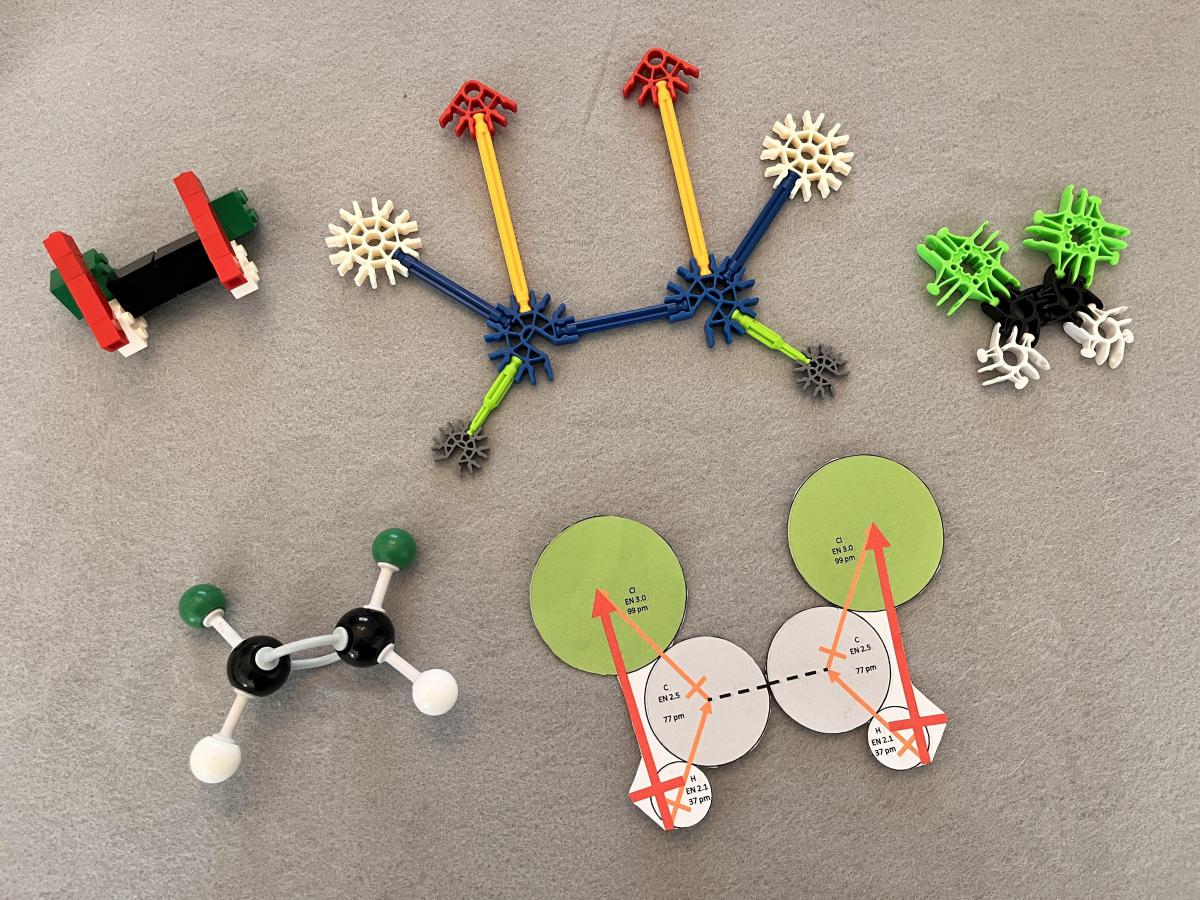

Figure 3 shows models of cis-1,2-dichlorothene and dipole vectors for portions of the molecules, using the same systems as those shown in Figure 2. In the cis molecular geometry, these dipoles for the half-molecules point in the same directions, do not cancel out, and make polar molecular models.

Figure 3. Models of polar cis-1,2-dichloroethene: (TOP LEFT) LEGO bricks, including dipole vector representation, (TOP MIDDLE) K’Nex, including dipole vector representation, (TOP RIGHT) Lux Blox, (BOTTOM LEFT) molecular model kit, and (BOTTOM RIGHT) paper model including dipole vector representation.

All of the models described so far represent planar molecules. An additional challenge seems to arise when analyzing dipoles associated with three-dimensional molecules. Part of this struggle seems to be related to visualizing these three-dimensional molecules based on two-dimensional representations on paper. Perhaps the representation that challenges my students the most is a tetrahedral molecule with two of one kind of corner atom and two of another kind of corner atom, for example, dichloromethane CH2Cl2. This problem seems to be most pronounced when the molecule is drawn as a flat in a square planar shape. (I sometimes call flattened two-dimensional representations of three-dimensional structures the roadkill representation.) When the chlorine atoms are adjacent to each other and the hydrogen atoms are adjacent to each other (much like ligands in a cis geometry in a square planar complex, or in the cis-1,2-dichlorethene molecule described above) the bond dipoles do not appear to cancel out and the molecule can be readily visualized as polar. When the chlorine atoms are drawn across from each other and the hydrogen atoms are drawn across from each other (much like ligands in a trans geometry in a square planar complex, or in the trans-1,2-dichlorethene molecule described above) the bond dipoles appear to cancel out and the molecule can appear to be nonpolar, but this is not really the case. Students should be reminded that the overall molecular dipole in this representation is pointing perpendicular to the plane of the flat molecular representation. Here three-dimensional models can be very helpful, especially if the models also have a way to represent the dipoles.

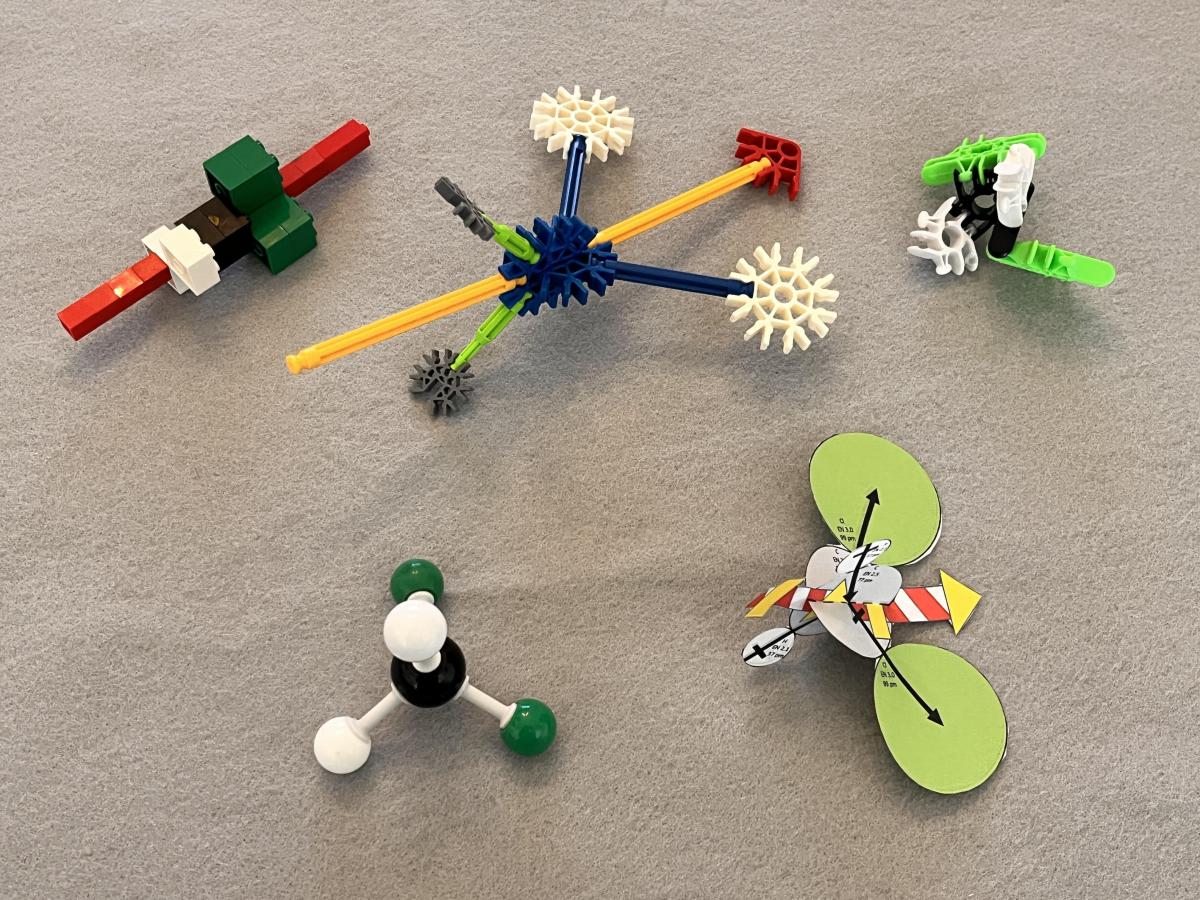

Figure 4 shows models of dichloromethane made using LEGO, K’Nex, and Lux Blox building systems, as well as models made from a typical molecule building kit and paper. Figure 5 shows an alternate representation of dichloromethane using Lux Blox, which is not in the same style as the Lux Blox models in Figures 2, 3, and 4, but makes an excellent tetrahedral shape. The LEGO, K’Nex, and paper models in Figure 4 also have representations of dipole vectors. In a way, this is reminiscent of the 1,1-dichlorethene molecule described above with vectors bisecting the angle formed by the carbon-hydrogen bonds and bisecting the angle formed by the carbon-chlorine bonds. The dichloromethane models can be thought of as having a sort of 90° twist in their structure relative to the 1,1-dichloroethane structure.

Figure 4. Models of polar dichloromethane: (TOP LEFT) LEGO bricks, including dipole vector representation, (TOP MIDDLE) K’Nex, including dipole vector representation, (TOP RIGHT) Lux Blox, (BOTTOM LEFT) molecular model kit, and (BOTTOM RIGHT) paper model including dipole vector representation.

Figure 5. Alternative Lux Blox model of dichloromethane.

Classroom Applications

What actually started this blog post was me holding up a large tetrahedral model in class and clumsily holding pencils to it to represent dipole vectors, as I have done many times in the past. Thinking about how to make a more stable model to show to the class, I developed a wooden model of dichloromethane, shown in Figure 6, made from wood that was cut with a scroll saw and colored with markers.

Figure 6. Model of dichloromethane made from wood cut with a scroll saw, with (LEFT) marked wood and (RIGHT) assembled model.

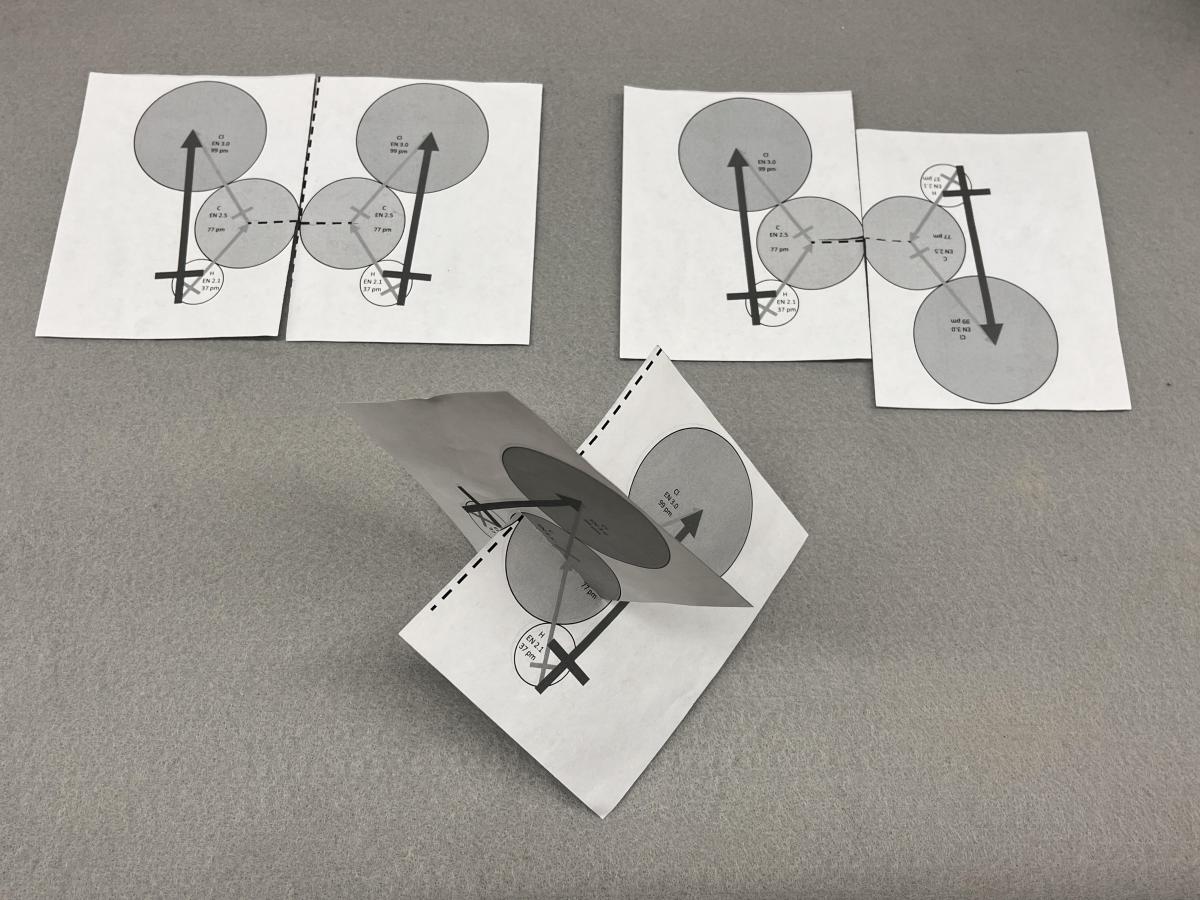

I passed this model around in my classroom, but it was only one model. I then sought models that could be mass-produced inexpensively for my classes. Laser-cutting materials could produce many models reproducibly, and, if wood or cardboard were used, sustainably. Paper models are flimsier, but they can be mass-produced with additional information using a photocopier, and they can be cut out by students. I printed out double-sided sheets of the patterns shown in Figure 7. Each rectangle is a quarter sheet of typical printing paper, and is printed on both sides with patterns representing a half of a molecule. The pattern consists of circles representing a carbon, a hydrogen, and a chlorine, with electronegativity values, atomic radii, and dipole vectors along each bond and for each trio of atoms on the rectangle. Pairs of the rectangles were handed out to the students in class to assemble in various ways. When the rectangles are placed together representing cis-1,2-dichloroethene as shown in Figure 7 (top left), the vectors associated with each half molecule are pointed in the same direction (not canceling out) and the molecule is polar. When the rectangles are placed together representing trans-1,2-dichloroethene as shown in Figure 7 (top right), the vectors associated with each half molecule are pointed in opposing directions (canceling out) and the molecule is nonpolar. When the rectangles are placed together representing dichloromethane as shown in Figure 7 (bottom, note the carbon circles are crossed though each other), the vectors associated with each half molecule are pointed in differing directions but not canceling out and the molecule is polar. The Supporting Information contains templates that can be used to build paper models of 1,1-dichloroethene, trans-1,2-dichloroethene, cis-1,2-dichloroethene, and dichloromethane. The files are two pages long and are designed to be printed double-sided.

Figure 7. Models of simple chlorinated hydrocarbons and dipole vectors from a double-sided half sheet of paper: (TOP LEFT) cis-1,2-dichloroethene, (TOP RIGHT) trans-1,2-dichloroethene, and (BOTTOM) dichloromethane.

It can be noted in the classroom that dichloromethane has uses as a solvent, but is problematic to health and environment, and its vapors can easily spread through the air. For example, dichloromethane release into the atmosphere from China has been predicted to slow the healing of the Antarctic ozone hole.4 It has even been detected in the air in the International Space Station.5 At one time, dichloromethane was a very useful solvent for my research. However, its use is being restricted by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency due its toxicity issues.6 Switching to alternative, less hazardous solvents can be connected to the field of Green Chemistry. One of the Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry is switching to Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries.7 A Chemical & Engineering News article about the coming changes in the use of dichloromethane was distributed to my classes and my students were asked to look up the health hazards that it listed. This connection to chemical hazard was part of a larger assignment about polarities and other properties of selected simple chlorinated hydrocarbons. Students were given a table with names of several simple halogenated hydrocarbons and instructed to use Wikipedia to find the formula, dipole moment, boiling point, and the log P (log of the concentration in nonpolar solvent to concentration in polar solvent) for the compounds. They were asked questions about the relative importance of intermolecular forces - London dispersion forces, dipole-dipole forces, and hydrogen bonding - on their boiling points. None of the compounds form hydrogen bonds, and careful examination of the boiling points reveal that London dispersion forces have considerable impact on intermolecular forces relative to dipole-dipole attractions. Students were also asked to predict, based on the log P values they found, whether the compounds would dissolve more in fatty or aqueous tissue in the body. The positive log P values indicated that these chlorinated hydrocarbons (even polar compounds) were more soluble in fatty tissues. The Supporting Information contains a file of this chlorinated hydrocarbons properties assignment. The one- or two-carbon chlorinated hydrocarbons in the assignment, and in many cases their dipole vectors, can be modeled using toys or paper, which can be used to help reinforce concepts associated with polar and nonpolar molecules.

Safety

Small children could possibly swallow units of building systems. Consider the hand-eye coordination of individuals being asked to cut paper to make models.

Acknowledgements

I thank Dennis Campbell for use of his scroll saw and his help with cutting the wooden model, and Mike Acerra for helpful suggestions and contributions of Lux Blox. This work was supported by Bradley University and the Mund-Lagowski Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry with additional support from the Illinois Heartland Section of the American Chemical Society. The material contained in this document is based upon work supported by a National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) grant or cooperative agreement. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of NASA. This work was supported through a NASA grant awarded to the Illinois/NASA Space Grant Consortium.

References

1. Campbell, D. J.; et al. Exploring the Nanoworld with LEGO Bricks [Online]; Bradley University, Peoria, IL, 2011. https://education.mrsec.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/283/2017/07/Le... (accessed December, 2024).

2. K’Nex website. https://www.basicfun.com/knex/ (accessed December, 2024).

3. Lux Blox website. https://luxblox.com/ (accessed December, 2024).

4. An, M.; Western, L. M.; Say, D.; Chen, L.; Claxton, T.; Ganesan, A. L.; Hossaini, R.; Krummel, P. B.; Manning, A. J.; Mühle, J.; O’Doherty, S.; Prinn, R. G.; Weiss, R. F.; Young, D.; Hu, J.; Yao, B.; Rigby, M. Rapid increase in dichloromethane emissions from China inferred through atmospheric observations. Nature Comm., 2021, 12, Article number: 7279.

5. Perry, J. L.; Peterson, B. V. Cabin Air Quality Dynamics On Board the International Space Station. (accessed December, 2024).

6. Vasquez, K. “A reckoning for methylene chloride in academic labs.” C&EN, 2024, 102 (21), 22-27.

7. Compound Interest. The Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry: What it is, & Why it Matters. (accessed December, 2024).

Supporting Information

Attached are PowerPoint files of templates to build paper models of 1,1-dichloroethene, trans-1,2-dichloroethene, cis-1,2-dichloroethene, and dichloromethane. The files are two pages long and are designed to be printed double-sided. Also attached is a Word file assignment addressing polarities and other properties of selected simple chlorinated hydrocarbons.