It is often said that writing is a window into a person’s thinking. As teachers, we must know what our students are thinking in regards to the concepts we teach. The whole point of the pedagogical approach promoted by the NGSS movement is to help the larger science education community get students thinking more, and more deeply about science content.

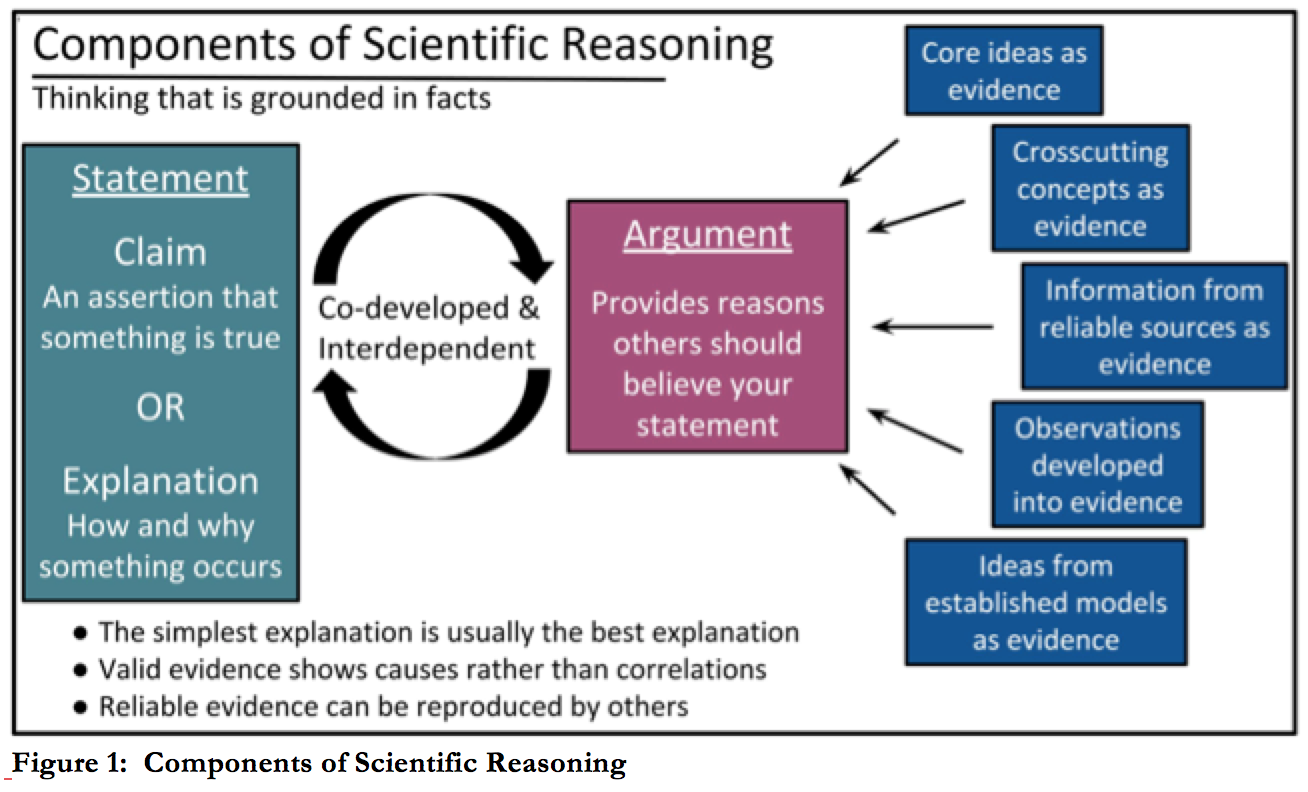

I think we should be asking our students to make written or verbal statements in our classes very often. In science class, this type of communication is typically in the form of a claim about what a result means or an explanation about how something works the way it does. In either case, the claim or explanation needs to be supported by thinking that is grounded in facts and logic.

The CER Scaffold: Helpful and Hindering at the Same Time

The Claim, Evidence, Reasoning (CER) scaffold has been widely adopted by science teachers. While I think the CER scaffold has provided some much needed help to support writing in science, my students and I have also found it to be confounding. This is because it separates evidence and reasoning from each other when in reality evidence is a critical part of reasoning (for more comments on this, see my previous post What is Reasoning?). Evidence is not something that should be considered separate from reasoning since reasoning is really a combination of evidence and additional commentary that attempt to convince others why a claim or explanation is plausible. I prefer to call reasoning an argument. Others call it justification (see Arguing Density by Stephanie O’Brien).

Some writing prompts we give our students are more suited toward claims: “What is the optimal mixture ratio of H2 and O2 to propel a rocket?” Other writing prompts we give are more suited toward explanations: “Why does Kona typically get onshore winds in the late morning and afternoon?” I think an argumentative writing piece consists of two parts, not three parts as suggested by the CER scaffold: 1 - the statement (which is a claim or explanation) and 2 - the argument. Instead of claim, evidence, and reasoning think statement and argument.

Science Reasoning Rubric

Building upon these thoughts and my revised Components of Scientific Reasoning figure from What is Reasoning? (see Figure 1), I put together a Science Reasoning Rubric that can be used for many writing prompts in a Chemistry class. It can be used whether a prompt is more suited toward a claim or an explanation (see Figure 2 - also available in the Supporting Information). Together, I think these documents help support students better through the argumentative writing process than CER does. I like that the rubric can be used for lots of the writing tasks students will encounter in a Chemistry class. This means students get used to seeing it, and this consistency is helpful as students write explanations and claims throughout the year.

What Counts as Evidence?

One question that may come up a lot is, “What counts as evidence?” As shown in Figure 1, evidence can be multi-faceted ranging from core ideas to models to observations or raw data. Before students start a writing prompt, it may sometimes be helpful to guide them toward what could be considered evidence for the task by pointing them toward relevant core ideas, cross-cutting concepts, models, data, etc. This is up to teacher discretion and the art (i.e. challenging part) is to provide this guidance without giving too much away to the students. I shared my own working list of core ideas in a previous Chemed X blog post, Toward an Accessible Set of Chemistry Core Ideas to Help Students Make Sense of Phenomena.

Another thing I want to note here is that the statement doesn’t necessarily need to come first and then the argument second in a written piece. As shown in Figure 1, the statement and argument should be developed together and in an argumentative piece of writing, it is perfectly acceptable to jump back and forth between comments that establish a claim or explanation and commentary providing reasons it should be believed.

Log into your ChemEd X account to access the two documents available in the Supporting Information: The Science Reasoning Rubric and the Components of Scientific Reasoning

NGSS

Constructing explanations and designing solutions in 9–12 builds on K–8 experiences and progresses to explanations and designs that are supported by multiple and independent student-generated sources of evidence consistent with scientific ideas, principles, and theories.

Constructing explanations and designing solutions in 9–12 builds on K–8 experiences and progresses to explanations and designs that are supported by multiple and independent student-generated sources of evidence consistent with scientific ideas, principles, and theories. Construct and revise an explanation based on valid and reliable evidence obtained from a variety of sources (including students’ own investigations, models, theories, simulations, peer review) and the assumption that theories and laws that describe the natural world operate today as they did in the past and will continue to do so in the future.

All comments must abide by the ChemEd X Comment Policy, are subject to review, and may be edited. Please allow one business day for your comment to be posted, if it is accepted.

Comments 3

great thoughts

Dustin,

I've read (and re-read) both your posts related to science reasoning and so much of what you have said reflects many of my own struggles and thoughts on the matter. The struggles both you and your students have identified when it comes to differentiating evidence vs. reasoning have taken place in my class throughout the past couple years as well and it can be incredibly frustrating. I can't tell you how many times even my most capable students have expressed confusion about where certain information should go. Though I knew the framework was a step in the right direction, I had always felt something was missing in it or it needed to be modified in some way. Your posts have helped me realize what needs to be modified within the framework. I absolutely love the rubric you developed and shared in this post and I definitely plan to start shifting my approach when asking students to make claims/explanations. Both posts you have written on reasoning are great and deserve much more attention. Keep providing great thoughts and resources on these topics! Thank you!

by the way...

I meant to ask you a couple things...

1) I noticed your science reasoning rubric doesn't include accuracy for the claim/explanation. When scoring a student's claim or explanation, do you take into consideration whether it's accurate (correct) or not? For example, if students are asked to identify an unknown substance and a student makes the claim that "unknown #2 is NaCl" when it's actually CaCl2, does that negatively impact their score with respect to the claim?

2) By switching from a distinct C-E-R approach to a Statement-Argument one, do you find that students' argument sections still have a consistent and rational "flow" to them? For example, do students tend to include their raw data, observations, etc. (evidence) at the beginning of the argument section or is it sort of scattered throughout?

3) If you have any student examples (or ones that you have made) of this Statement-Argument approach, would you mind sharing?

Re: by the way...

Hi Ben, Thanks for the comments!

1) I know there are lots of opinions on this, but I personally place more emphasis on how well the claim/explanations are supported rather than correctness. In other words, I value the argument more than the claim/explanation itself. I believe by doing so, I am more closely modeling how science in real life is done. Real scientists doing real science usually don’t know the correct answers to their problems, they collect their observations and make arguments supporting their interpretation of their data. For the types of tasks we typically do in High School, I feel like if the claims/explanations are well supported with strong arguments they are usually correct, or close to correct, anyway.

2) I find the writing flows more naturally by removing the distinct sections of C-E-R and giving the students the freedom to place their evidence in their writing where it makes sense to them for a specific prompt. Some students tend to keep the evidence all together and then make an argument and other students tend to jump back and forth between stating a piece of evidence supporting it. I think the statements that jump back and forth between evidence and argumentative statements often flow better than if all the evidence is bunched together. This does depend on the student and the task though. After reading a student response, I like to consider the writing piece as a whole and what matters most to me is to what extent the author used data and observations combined with facts and logic to convince me to believe what he or she has written, regardless of where the evidence actually appears in the writing.

3) I tend to give student work back to students, but I will collect some samples from the next few tasks we do and send them to you. If I forget, please reach out to me again:)