The flipped-classroom approach to education is undoubtedly popular, with consistent growth in the number of related books, conference sessions, and educator network memberships.1 Although challenges with the approach are reported, the advantages are far more widely claimed. Many of the advantages are related to pedagogical contributions, such as flexible learning, peer-based learning opportunities, and other active-learning strategies. Although active-learning may not be any more beneficial in a flipped classroom compared to a traditional classroom2, it is clear that a flipped class can increase the frequency of active-learning opportunities.3

In this post, we'll explore in-class activities, and address the following questions:

-

What are the most popular in-class activities used in a flipped classroom?

-

How can a class period be structured to make the most of class time and incorporate many of these activities?

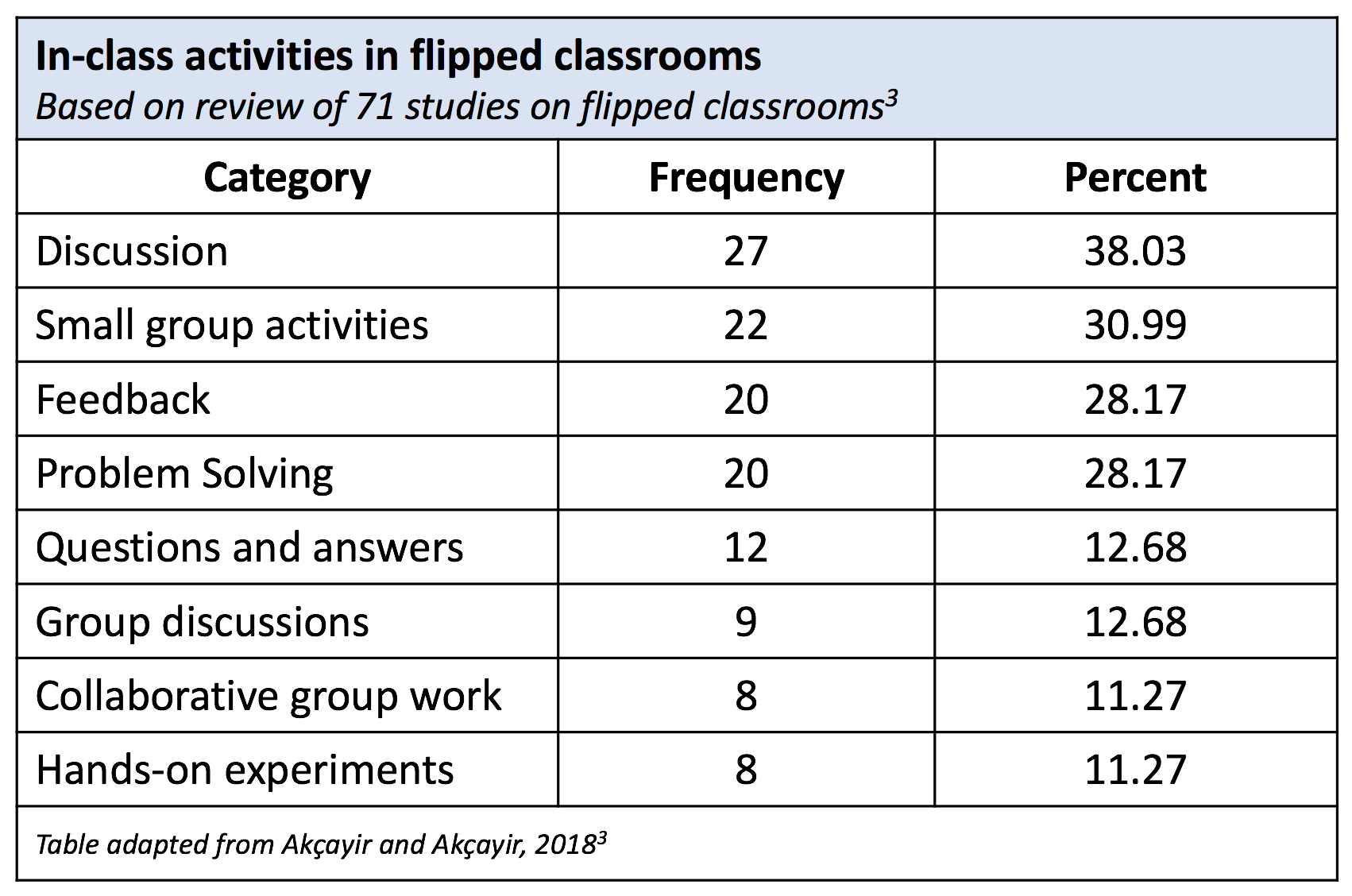

In a 2018 literature review, Akçayir and Akçayir conducted a large-scale systematic review of the research on the flipped classroom since 2000.3 In this study, they explored the advantages, challenges, and categorized the types of in-class and out-of-class activities in flipped classrooms. They found that the most popular activities were student-centered, including discussion, small group activities, feedback, problem-solving, and collaborative group work (see table 1). Each of these activities falls under the umbrella of active-learning, which is different from traditional lecture-based learning. In more traditional-learning models, students are passively engaged with the content as the majority of communication comes from the instructor. During active-learning, students are much more involved in the learning process. They actively participate in thinking about the content and communicating their learning approach.4

Table 1: Frequency of in-class activities in flipped classrooms.

In the context of chemistry, I have found some of these activities to be more beneficial than others. Over the years, I’ve refined a framework to routinely incorporate many of these strategies into a single class period. Although I teach within an 80-minute block period, this model could be adapted to work in shorter class periods by splitting the framework over two days.

As a governing principle, consistency in assignments and methodology is critical. In a recent study about student engagement in a flipped classroom, Gilboy et al. found that too much variation of in-class will decrease their effectiveness because students tend to focus on the learning strategy instead of the content.5 Thus, I structure every week in the same way (see figure 1). I try to organize the content for a week within a broader theme. For example, molecules may represent a broad theme for the week, and each class period explores content that's related to that theme. For the theme of molecules, we would learn to draw structural formula, determine three-dimensional structure with VSEPR theory, and identify bond and molecular polarity. At the end of each week, knowledge is assessed with a quiz (I call it the Learning Check). At the beginning of the week, I provide students with a Practice Learning Check, which I believe is imperative, because it directs their focus on the essential knowledge skills that they should construct by the end of the week.

Figure 1: General weekly framework for a flipped classroom.

Similarly, each class period follows a general framework (see figure 2). Each class period includes the following components:

- Entrance Card

- Group Thinking

- Workshop

- Learning Tasks

- Exit Card

Figure 2: General class period framework for a flipped classroom.

Entrance Card

Before class, students prepare by taking notes as they watch a video tutorial and/or read corresponding textbook pages. The related knowledge and skills are assessed at the start of each class period with a small assessment, called the entrance card. The entrance card is a short, 3-5 question quiz that consists of problems related to the topic for the day. Additionally, I usually include a question that reviews the previous days' content. Once everyone has finished the entrance card, students trade their papers, and we grade them together. The entrance card is valuable not only as a way to check that students completed their prep work but also as a form of instant feedback on their learning.

Group Thinking

Next on the agenda is the group thinking activity. I subscribe to a social constructivist theoretical understanding of learning, which suggests that knowledge is best constructed within a cultivated social environment. Within this environment, peers interact by challenging and supporting one another as they process the content.6 Profitable group thinking activities are challenging and non-linear activities, causing students to think more deeply about the content and struggle in cooperation with one another. By design, strong students are compelled to assist struggling students.

As an example of a group thinking activity, when learning about periodic trends, I use a data analysis activity that is similar to the New York Times educational tool, What’s going on in this Graph. Students analyzed graphs that communicated ionization energy as it related to other variables such as the atomic number and the removal of subsequent electrons (see supporting information). This activity only took about 10 - 15 minutes to complete, and it prompted a conversation that defined ionization energy, discussed reasons why an electron’s proximity to the nucleus affects the ionization energy, etc.

Workshop

After group thinking, we enter into a micro-lesson that I call the “Workshop.” This lesson targets misconceptions and reinforces key points. Students who score over 80% on the entrance card can “test out” of the workshop so that they can prepare for the next class period or work on practice assignments. In general, students who “test out” of the workshop, correct their misconceptions during the group thinking activity, and the workshop seems to be more impactful with a smaller number of struggling students.

Learning Tasks

Each week, students choose to complete tasks from a list of assignments. In general, the tasks come in two forms: (1) practice problems for students who need to spend more time on basic knowledge and skills and (2) POGIL activities so that students can develop a deeper conceptual understanding of the material. Although students have a choice, I prefer that they work in groups to complete the POGIL activities.

Exit Card

Finally, the class ends with another assessment called the exit card. The exit card is in a similar format to the entrance card; however, it is optional because I only keep the better score between the two. Students who want to improve their entrance card score opt to take the exit card. I find an average increase of around 50 - 75% between the entrance and exit card scores. Furthermore, I find that these scores are great data points when talking with students and parents about their growth in the course.

Although this format has worked well in my flipped classroom, I recognize that sticking to a consistent framework can sometimes result in a dull or rigid curriculum. I think that I balance rigidity with variety in the group thinking and learning tasks. However, I am interested to learn about how other teachers structure their flipped classroom. If you have thoughts or suggestions related to in-class activities, please leave a comment, I’d love to learn more.

References

- Network, F. L. (2014). Flipped Learning Continues to Trend. Retrieved from https://flippedlearning.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Speak-Up-FLN-2014-Survey-Results-FINAL.pdf.

- Jensen, J. L., Kummer, T. A., & Godoy, P. D. D. M. (2015). Improvements from a flipped classroom may simply be the fruits of active learning. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 14(1), ar5.

- Akçayır, G., & Akçayır, M. (2018). The flipped classroom: A review of its advantages and challenges. Computers & Education, 126, 334-345.

- The University of Michigan, Center for Research on Learning and Teaching. Introduction to Active Learning. Retrieved from http://www.crlt.umich.edu/active_learning_introduction.

- Gilboy, M. B., Heinerichs, S., & Pazzaglia, G. (2015). Enhancing student engagement using the flipped classroom. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 47(1), 109-114.

- Palincsar, A. S. (1998). Social constructivist perspectives on teaching and learning. Annual review of psychology, 49(1), 345-375.

All comments must abide by the ChemEd X Comment Policy, are subject to review, and may be edited. Please allow one business day for your comment to be posted, if it is accepted.

Comments 8

The 0 percenters

What do you do with those students who score the 0% on the entrance card? I ask because while I agree that it is about understanding, I am also fighting with students who have no idea how to work hard to get concepts.

0 percenters

I completely relate to the struggle that you described. I've tried a few different tactics to limit consistent low entrance card scores for students. Here are two of the strategies that have worked best:

(1) Although I take the higher score between the entrance/exit card for the day, the entrance card score can be a significant contribution to the student's engagement/participation grade. If they score low on the entrance card, it shows that they did not prepare for class and will not be able to contribute to group discussions and activities. In some schools, the participation/engagement grade is meaningless or nonexistent. However, in the school that I teach, this is a significant grade and it motivates most students to prepare well.

(2) When engagement/participation isn’t as meaningful, I have recorded an average between the entrance and exit card scores for their daily grade instead of taking the highest. As I’m sure you know, it’s difficult to motivate students when something “doesn’t count as a grade.” So, making the entrance card count towards their grade for the day is a pretty good motivator.

I don’t think I have ever experienced a class period where 100% of my students had properly prepared for the lesson. I’ve gotten close with the strategies that I mentioned here, but I welcome other thoughts. I’m sure someone out there has a “secret weapon” to encourage student participation in a flipped classroom.

My Flipped Structure

Thanks for sharing your ideas on flipped learning. It's nice to know there are other teachers out there flipping their classes.

I have been using the flipped model in some format for at least 7-8 years. It was nice to see how you structure your day. I follow a similar routine. Most days begin with what I call whiteboard problems. The whiteboard problems are very similar to your entrance slips, although they are not graded. Students are encouraged to work in groups of two. The whiteboard problems consist of 2-3 questions, based on the previous night's video lesson. I like this because I can quickly see where the students are as a whole. After the whiteboard problems are complete we then work on an activity. The activity might be lab-based, POGIL, etc. The period ends by giving students time to work on whatever topic is giving them the most trouble. I have a bank of questions on Canvas that the students are free to work on. I used the question bank to create online practice sets for the students to work on at their own pace. The practice sets can be taken repeatedly for mastery with few repeats. We then follow up with a quiz later in the week and of course a test that covers the entire unit.

The biggest problem I face is getting the students to work on the practice sets. I want my students to understand that success comes from hard work and discipline. It's frustrating because so many of my students waste this portion of the class. I walk around the room offering help and guidance. I routinely encourage them to work together and support one another. Don't get me wrong. I do have a number of students who work hard, ask questions and help each other but as the years go by I'm finding fewer and fewer students who are willing to do what it takes to succeed. I teach AP and honors chemistry. My AP students love the flipped model. I think it has to do with their maturity and work ethic. They quickly realize that if they watch the videos, take notes and come in ready to work they will understand the material and feel more confident. My honors course, on the other hand, is very different. Some days it is a struggle to get them to do any sort of productive work. Some kids don't bother to watch the video lessons. If they do they refuse to take notes. A large number of them want me to do the problems on the board while they watch. They think because I'm not lecturing at them then I'm not teaching them. Their lack of effort blows my mind.

Other than making them chase points, is there another way to motivate this generation of students? When I first started flipping my class I had way more students who took advantage of this method of instruction.

Thanks again.

Flipped structure

Thanks for sharing the way that you implement a flipped class. I like the idea of starting class with whiteboarding in groups. I occasionally have "group entrance cards" which provide a similar effect to your whiteboarding.

As far as motivating students, I'm not sure that I have found that answer yet. To be honest, I still find grades to be the best motivational tool. Grades still seem to the "currency" that students understand and relate to best. I have found that just counting the entrance cards (or whiteboarding activity) as a grade will get most students to buy into watching the videos, although, there always seems to be a few students who will just never do homework no matter what it is.

I Stopped Using the Flipped Classroom Model

I jumped on the flipped classroom bandwagon and attended a CUE conference centered on flipped classrooms which featured Bergman and Sams teaching us their methods, showing us how to make videos, how to set it all up, etc. It sounded great, an amazing way to differentiate instruction. I learned how to make videos, which was a huge flop. As it turns out, I am much more exciting when I am interacting with students in person than when I stare into a video camera.

Students did feel like I wasn't doing any work to teach them, when in fact I was of course doing a massive amount of work switching everything over to the new format and keeping track of where students were in their work, as well as working with small groups in class who needed more help. I still felt that it made a difference that students felt like they are being taught, and that should not be dismissed. They really do want that interaction with and direction from the teacher. That is what makes our jobs necessary. Silicon Valley tech gurus and school privatizers would love to sell us their products and eliminate teachers, respectively; however it is the interaction that makes a big difference. We can have interactions in class after students watch a video or read a selection the night before, but for whatever reason it isn't the same thing, especially if 100% of the class was not participating. Some people would argue that individualizing instruction to that extent would mean hiring of only an uncredentialed, much cheaper aide to guide students along through self-study curriculum.

Indeed there are always students who do not do their work at home and come to class unprepared. There is no way to get 100% participation. This is one reason I no longer use the flipped model. When the instruction is delivered in the classroom, I have control over motivating and/or insisting that students participate. It became absolutely unacceptable to teach in a way where I knew that some students would not learn as much. If I just keep going knowing that some students aren't doing it, then what am I doing? Not my best. I need to find another way. It is an equity issue if these students have a level of trauma or dysfunction caused by poverty, parent alcoholism, or depression, for just a few examples, that prevent them from completing assignments.

I am still the "guide on the side" in most cases. We use a lot of guided inquiry in my classroom, through POGIL, Living By Chemistry textbook curriculum which are very good guided inquiry, or through phenomena-based development of models. Working in teams to develop ideas in class has been much more productive for my students than pre-class preparation and discussion or activity. And I find it much more efficient to do a guided inquiry activity in class, and then have them process by doing an assignment at home after, rather than before, so they can visualize concepts they obsesrved in class and have a bank of knowledge to pair with the vocabulary and description of the concepts in the homework. They have a better framework of knowledge in which to integrate new concepts. This is basic Ed Psych 101.

Adopting flipped class

I am currently in a graduate teacher training program and I have taken much interest in the flipped class model. Actually, my graduate classes are much like a flipped classroom already. Much of the reading and thinking are done prior to the class and we come to the class with knowledge about what we will be going through in the class. I think it's a very effective system. However, we are graduate students who brings a level of maturity to learning; it does take a bit of discipline to make sure readings are done and writing on the class discussion board is completed. There is some going over the materials in the class but the majority of the time is spent on discussing clarification questions and share-outs.

I sort of see the point of the above comments that when students come unprepared, those students may be in a danger to fall behind and continue to do so further down the road; what do you think is the remedy for this, in the context of the flipped class model? I know you mention the "entrance card" as a motivator but what if some students are persistently unprepared but perhaps might engage better in-class delivery of materials? Would you consider mixing it up with some in-class lecture as a way of "force-feeding" those students?

Thanks,

Byungmoon

Flipped Classroom: A Framework for In-Class Activities

Hi Josh, late to the party, but I have a question. For your "Learning Tasks" does that include problem solving, conceptual work and lab work or is it something different? I too am looking for new ways to hold student accountable for the flipped homework and I like the workshop idea. '

Also wondering how you'd make this work in a 50 minute classroom.

Thanks,

Liz Hamann

Hi Liz!

Hi Liz!

I continually revisit ideas for "Learning Tasks." These days, I have been focusing more on problem solving practice. For lab work, I treat lab as a different course with my chemistry course. So labs are outside of this framework.

As for making this system work in a 50-minute class period... I split lessons up over multiple days. So maybe on day 1, we all work on a POGIL together in class and then on day 2 we hold the workshop.

Let me know what you find works well!

-Josh