I have a confession to make: I’m a mean teacher. I make my junior chemistry students learn the element names and symbols--all one hundred and eighteen of them.

You might say that’s impossible, a waste of time, or downright unnecessary in today’s age of information at your fingertips. When I was a new teacher, I might have agreed. I started my first year teaching in November following a long term sub who had covered atomic structure and bonding--you know, the fundamentals.I decided we could get right to chemical nomenclature and then writing and balancing chemical equations. You can probably guess how that worked out, since I’m writing this.

I soon realized that asking my students to write and interpret chemical formulas without knowing the symbols for the elements was akin to asking someone to spell words and write sentences without knowing the alphabet. Over the past few years I have tried numerous tactics from making flashcards to having quizzes over progressively larger chunks of elements. Early on I considered choosing only certain elements that needed to be memorized but soon decided that any list I would choose would be arbitrary at best and leave my students unexposed to vast swaths of the periodic table. I certainly didn’t want MY students mistaking dilithium, vibranium or unobtanioum for real elements!

Those first few years, I had significant resistance from students to learning all the elements. However, once I proved that it could be done (I flexed my geeky bravado and recited all the elements from memory) they came around to the idea as a challenge worth accepting. My students still find chemical nomenclature and writing and balancing chemical equations challenging, but at least they know their alphabet first. Here are a few of the methods (in no particular order) I have found useful.

Flash Cards

It may sound simple, but one of the assignments I give the first week of school is to make a set of flashcards by hand. Even though there is an "app for that" as at least one student reminds me every year, the physical act of making the cards has immense value. I ask students to bring these cards with them to class regularly and as a filler activity will ask them to pull out their flashcards and quiz their lab partner.

Figure 1 - Element Flash Cards

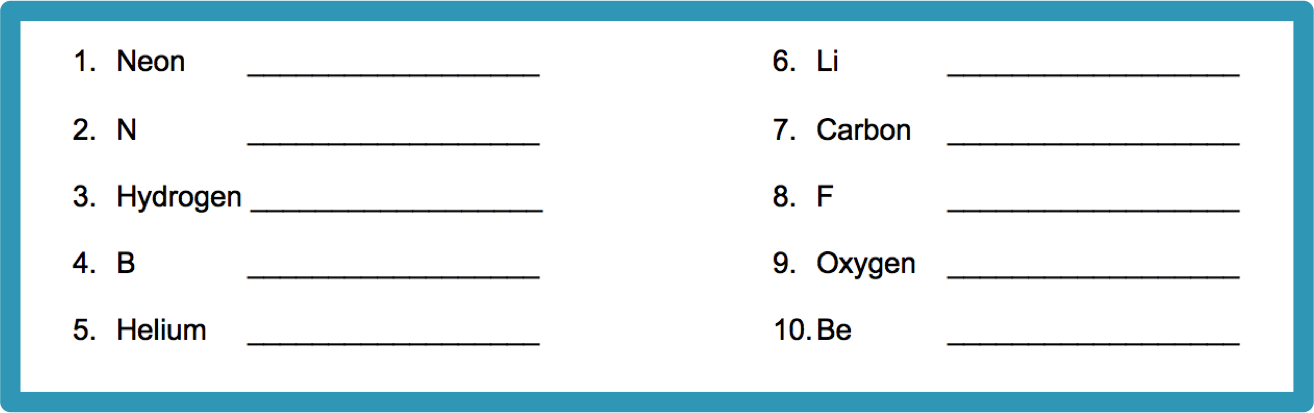

Cumulative Quizzes

How do you eat an elephant? One bite at a time. Inspired by this old joke, and my theology teacher next door neighbor who had students learn scripture memory verses, I broke the periodic table into chunks of 10-ish elements. Every two weeks, students are quizzed over the next ten elements plus a few elements from earlier on in the year chosen at random. Following this schedule, students know the vast majority of the elements by the first part of second semester in time to write chemical names and formulas. You can find some sample quizzes in the supporting information below. (Note: I have not updated these quizzes to include the most recent four elements since I am using Sporcle to create my quizzes now.)

Figure 2 - Sample Element Quiz

Periodic Table Battleship

Having fun is one of the best ways to learn, and my students actually like playing this game. You can find an explanation of the game here from the Huffington Post. You can use any version of the periodic table you like to make the game--I favor one with just the symbols. This is a great filler activity if you have an awkward 15-20 minutes, say before an assembly or early dismissal. I have included a periodic table for your use in the supporting information below.

Element Bee

Spelling bees are a staple of elementary school, though less commonly in high school. I frequently do an “element bee” with my classes, and while I don’t usually do spelling of the names with this game, of course you could play it that way. Everyone stands up and using my own set of element flash cards I give the first student an element name or symbol. If I give the symbol, they have to give the name, and vice versa. Again, this is a good filler activity, for like 5 minutes at the end of class.

Element Cherry Pie

Working in a PS-12 school (under one roof), I have an unusual opportunity to glean ideas from my colleagues from a variety of subject areas and grade levels. I picked this idea up from my colleague who teaches fifth grade. To play this game (chemistry style) you have the students stand in a circle. The first student is given the name of an element. They have to give the first letter and as the students go around the circle each gives the next letter. If they get the letter wrong they are out of the game and must sit down. The game continues around the circle until the element name is complete. The next person after the last letter says the name of the element, the symbol and “cherry pie.” That student is then out and sits down. The next student in the circle starts the next element. I haven’t given really any thought why it is called Cherry Pie...my best guess is that pies are...circular?

Sporcle

Again, inspired by a colleague, (this time our high school social studies teacher), I decided to experiment with using Sporcle as an alternative to cumulative quizzes this year as my school has gone to a one-to-one chromebooks program. This year instead of doing the cumulative quizzes I chose three different sporcle quizzes: element to symbol match, element by symbol, and element abbreviations and scheduled them in rotation once a month. Each month the bar is raised for how many elements are needed to earn full credit. This has been very successful this year!

CITATIONS

Sporcle, Inc. . (2007, January 30). In Sporcle. Retrieved from https://www.sporcle.com/

Touch Press Inc. (2018). In The Elements FlashCards. Retrieved from https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/the-elements-flashcards/id835885718?mt=8

Wanshel, E. (2016, October). In Mom Creates Periodic Table Battleship Game To Teach Her Kids Chemistry. Retrieved from https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/mom-creates-periodic-table-battleship-game-to-teach-her-kids-chemistry_us_5697f3d4e4b0b4eb759da83b

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Mr. Benjamin O'Hearn, JD, Former Teacher of Theology

Mrs. Kaye Sandborn, Teacher of Social Sciences

Mrs. Gayle Thelen, Teacher, 5th Grade

NGSS

Students who demonstrate understanding can use the periodic table as a model to predict the relative properties of elements based on the patterns of electrons in the outermost energy level of atoms.

*More information about all DCI for HS-PS1 can be found at https://www.nextgenscience.org/dci-arrangement/hs-ps1-matter-and-its-interactions and further resources at https://www.nextgenscience.org.

Students who demonstrate understanding can use the periodic table as a model to predict the relative properties of elements based on the patterns of electrons in the outermost energy level of atoms.

Assessment is limited to main group elements. Assessment does not include quantitative understanding of ionization energy beyond relative trends.

Examples of properties that could be predicted from patterns could include reactivity of metals, types of bonds formed, numbers of bonds formed, and reactions with oxygen.

All comments must abide by the ChemEd X Comment Policy, are subject to review, and may be edited. Please allow one business day for your comment to be posted, if it is accepted.

Comments 13

Memorization and improved understanding

Hi Jordan,

I was wondering what benefits you’ve seen as a result of these activities? You mention in the blog your students still struggle with the application tasks of balancing and nomenclature so I’m wondering how the memorization pays off. I currently don’t make my first years memorize any elements and allow them a periodic table on all assessments. I have had them memorize names and symbols in the past, but only a select few.

Im also curious how much time you spend on these activities.

Thanks in advance!

Benefits

Wow! I had no idea this topic would be so interesting to people!

I'd say that the biggest benefit I've seen is increased confidence. Before I started requiring students to learn the element names and symbols students acted throughout the entire year as if what we were learning was an impossible impenetrable mystery that could never be grasped. While I wouldn't say that students never find nomenclature or balancing equations challenging, it isn't the gutwrenching slog it used to be. I too provide a periodic table on assessments (and of course have a huge one hanging on the wall too!) however I only give one with the symbols in the second semester. I wouldn't say I spend a lot of time on these activities. As I mentioned in the blog, most of these activities are outside of class or filler activities. The only thing that takes any real time in class is the quizzing. When I paper quizzes it would be about 5 minutes at the beginning of class once a week for the first semester. Now that I do the Sporcle quizzes I do it once a month for the first semester(ish). Depending on the Sporcle version I use it takes from 5 to 15 minutes.

Thank you for joining the conversation.

Long term understanding

Hi Jordan,

The periodic table is a masterpiece of information and organization but after more than 25 years of teaching chemistry, I have not memorized all the elements. I began my career requiring students to memorize about 30 of the most common elements that we would deal with over the course of the year. I required them to memorize about the same number of ions. I also required students to memorize equations (like Boyle's Law, density, etc.) during the chapter they were introduced, but then allowing students to include those equations on a notecard on semester exams. That said, I have never been a fan of memorization. My goal has always been to help students develop conceptual understanding. Having been trained in Modeling Instruction, I have been happy to drop the memorization of equations. I have been pleased to see my students reason through relationships and ratios to solve problems without a memorized equation. I did try to drop the memorization of elements and ions as well, but found that my students spent so much time looking up element and ion names and symbols to put together formulas and equations, that they were just stumbling in the task of writing names and formulas. I know that having my students memorize my short lists of elements and ions will not make those names and formulas stick in their long term memory. But, after using them through the rest of the year, the most commonly used seem to end up stuck for the long term (or at least through AP chem). Aside from the few quizzes that I give students while working to memorize my short lists, I provide periodic tables along with a copy of the ions that I asked them to memorize. I have found that students do not rely on those resources as much after memorizing them. This allows for more focus on the task at hand and they have mastered formula and name writing much quicker than that year I did not require any memorization.

I am interested in finding out how many teachers do not have students memorize vs. those that require students to memorize either a short list or the entire table. I hope teachers will vote on the poll I created. I am also interested in reading comments about how other teachers feel about memorization of elements and ions.

Take the POLL

Hunt and Peck Chemistry

As far as students spending too much time looking up element symbols, I concur. It's like not knowing how to type. You will never type fluently if you have to hunt and peck for each key. I think that students are able to focus more on the mechanics and conceptual understanding of formula writing, and later equation writing and balancing if they are not so hung up on having to "hunt and peck" each element on the periodic table.

You may also be interested to hear that I shared with my senior AP Bio class that I wrote about this topic and that I am apparently in the minority of chemistry teachers who make their students memorize the element symbols and names. I asked them how they felt about it and they all said it wasn't hard at all especially when we would occasionally do games like those I wrote about in the post.

I sympathize, however...

I sympathize with wanting students to know the alphabet of chemistry, it can be frustrating when they don't. To that end, I do have them memorize a list of elements and then a list of common ions (both simple and polyatomic). However, I do not make this an end-all-be-all part of my course. I teach them a few memorization strategies (5 minutes tops), we take 1-2 quizzes on each (5 minutes each), and that's it. I do think students benefit from learning to rote memorize things, as long as the practice does not take away from a focus on conceptual understanding. I fully support all of what Deanna said in her comment. Do students forget some? Yes. Does that matter? No, the important ones stick becuase they are used so much.

I become very upset when I hear teachers say things like, "my students keep failing becuase they don't memorize their elements or polyatomic ions." Chemistry is a vast and beautiful subject, are you going to tell students they are not worthy to study it if they struggle to memorize a list of names and symbols with which they have just been introduced? What this says to me is that the assessments used are poorly designed. Are you assessing a student's understanding of stoichiometry, or of formula writing? Sure, maybe you have one stoich problem where students have to write a full equation from words to begin with, but if your entire assessment is structured that way you have not designed a useful or targeted assessment. For teachers of AP Chemistry: yes having these things memorized aids in fluencey, but with the removal of the old Question 4, students will no longer be required to write a chemical formula given a name alone.

You mention that you don't want your students unfamiliar with a large swath of the periodic table. I am personally okay if they are. 24 of the elements do not occur naturally and an even greater number never (or rarely) come up in a general chemistry course. If a student is ever curious, I ask them to reserach the element and bring back some fun "did you know" info for the class. Francium has a half-life of about 22 minutes, astatine is the rarest element on earth, etc. Neither would be useful in a general chemistry lab.

Memorization is not a bad thing, when used appropriately and not as an ends in itself. I am curious to see your responses to Erica on how much class time you spend on these activities and the benefits you observe.

Oh, you are absolutely right.

Oh, you are absolutely right. Students do forget some, but the ones they use frequently stick! I do also know what you are talking about when you refer to assessing skills separately. However, I do think that there is still a place for summative sort of assessment where it wouldn't be unreasonable to expect a student to pull together a variety of chemistry skills. For instance, I could ask questions on a quiz about stoichiometry simply assessing the calculations when provided with a balanced equation, and sometimes I do. However, I think it is also valuable to see if students can put the pieces together to write the formulas, predict the products, balance the equation and then be able to use the stoichiometric ratios in a conversion problem. Assessing separate skills in isolation is sometimes called for, but so is assessing that global "how does this fit together with the stuff I learned earlier this year" sort of thinking.

As far as the rare elements... I take my class on a spring field trip to the National Superconducting Cyclotron Lab (NSCL)and Facility for Rare Isotope Beams (FRIB) at Michigan State University, which is right down the road from us. That is really why I want them to be at least aware of synthetic elements, rare isotopes, and such. Last year was the first time and I think I will make it an annual trip. I was pleasantly surprised how some students got excited to see where "real science" is done. This is especially cool because particle physics is obviously not the focus of junior chemistry (or a high school physics class for that matter), but you never know if that is the thing that peaks the interest of a kid who wouldn't consider pursuing science as a career if they were unaware.

Thank you for joining the conversation!

What needs to be well-memorized

The question of memorization is one for which science has agreed upon a clear right answer. And the answer is: All frequently used fundamentals must be thoroughly memorized/automated/overlearned. For a recent paper that addresses the scientific consensus on this issue, search for “chemistry and cognition blog” and download the article at Post # 11. Other posts there may be of interest as well.

To work in “Chemistry Education” in 2018, it helps to have knowledge of two sciences: The science of molecular behavior, and the relatively new but consensus science of how the brain works and how it learns.

Cognitive science does not say to “memorize everything.” It does say: have them memorize enough fundamentals so that when trying to teach algorithmic procedures and concepts, the concrete examples you cite use familiar facts and relationships. Unfamiliar facts and relationships occupy slots in “novel working memory” that need to be left available for the unique elements of the problem that you want the brain to link conceptually.

Conceptual frameworks are built in the brain by wiring synaptic connections between neurons that store elements of knowledge. You can’t connect neurons until they contain elements of knowledge that have been well-memorized; stored in long-term memory. And storing the exact relationships of science and math in long-term memory takes repeated effort to recall the relationships, spaced over time.

What cognitive science says is needed for efficient learning is: First thoroughly memorize fundamental relationships, THEN use them to solve problems in a variety of distinctive contexts (including demonstrations and inquiry problems).

--Eric (rick) Nelson

What is being memorized in chemistry classes?

I'm curious about what, if anything, teachers have their students memorize. For example, while I do not require my students to memorize the element names and symbols, I do find it helpful to have my students memorize roughly 15 polyatomic ions (symbols, charges, and names). Upon telling my students to do so, I make it absolutely clear there is a difference between memorizing the symbols of the polyatomic ions and being fluent with using them. I strongly stress that my desire for them to memorize the polyatomic ions is the first step, but the end goal is for students to be fluent in the language of polyatomic ion symbolism. Are there any teachers that don't have their students memorize anything at all in their classes? I'd like to see a follow-up poll which surveys teachers if:

A) They do ask their students to memorize some things (formulas for equations, polyatomic ions, the periodic table, vocabulary, etc).

B) They never ask their students to memorize anything.

Learn about how the arrangement, not memorize

I do not have my students memorize the elements or polyatomic ions. I tell them that before I went back and got certification to teach, I worked as a chemist in a lab. If I forgot something, I had the skills to know where to look. That is the skill I want my student to have. To feel comfortable to understand the beauty of the periodic table, for example, why do polyatomic ions arrange the way the do?, the change in our idea of the model of the atom throughout history and what investigations or data was used in the discoveries. Using a modeling approach has really led my students to a deeper understanding of chemistry. When my students hear that they do not have to memorize it lifts them up and makes them more open to learning. They find that over time with use, they start to know more about the elements, their placement on the periodic table, why they form certain ions and why compounds join up.

Utilization over memorization

8th grade English taught me that. Utilization over memorization. Can't say I learned much else as I found out when I switched schools in 9th grade, but that's another story for another day.

Similar to what Deanna, Erica, and Tom mentioned, I have my students memorize very little and you'll see why in a moment. I do have freshmen Chem 1 students memorize 35 common elements (name and symbols) as well as 18 common polyatomic ions, which I find makes nomenclature go by a little bit more smoothly. Along with my department colleagues, I provide students with a laminated periodic table that has common polyatomic ions, activity series, solubility chart, and electronegativity values on the back. The goal is that students will demonstrate proficiency with learned skills rather than learned facts, especially in our Chemistry 2 course.

By the sounds of it, you teach a year-long course so having scaffolded learning targets for the elements throughout the year makes sense. You have the opportunity to hit that multiple times. In our district, Chemistry 1 is a semester-long course for freshmen and it currently covers lab safety and measurement, atomic theory, nuclear chemistry, periodicity, bonding, nomenclature, chemical reactions, and physical properties. Chemistry 2 is considered an elective and is taken primarily by juniors. Occasionally we get the sophomore or senior too. Chemistry 2 covers the quantitative aspect of the subject like stoichiometry, solutions, equilibrium, acids and bases, energetics, kinetics, gas laws, and sometimes redox/electrochemistry. As you might imagine, when Chemistry 2 begins we have to review atom counting and balancing equations. By this point, students have been out of the game for a year or two and have subsequently forgotten the difference between ionic and covalent bonds, not to mention nomenclature; students don't necessarily need to know bonding or nomenclature to tackle the applied mathematics aspect of stoichiometry, solutions, energetics, etc. It'd certainly make for increased scientific literacy but isn't required to demonstrate proficiency in applied mathematical skills.

I'm really interested to hear

I'm really interested to hear about the diverse types of courses everyone here teaches! I assumed (obviously naively) that most schools have chemistry as a course for upperclassmen only and as a yearlong course. I can't imagine the pace you would have to move at to do chem as a semester course! However, given that sort of time constraint, yes, not memorizing makes sense. I think you are right though in your assessment that my curriculum is scaffolded (even if I didn't consciously do that). One benefit I also have is that for most of my students I have them for three years in a row so I get to "scaffold" across years.

Memorizing versus Application

First, I teach at the community college level and have done so for over 25 years. I do not buy into the idea that students MUST memorize certain things in Chemistry. When I ask other Chemistry Faculty "Why?", I hear many say "Because I had to do this." I would compare that statement to hazing students in a fraternity as they give the same reasoning.

I do not have my students memorize anything as I provide then with all formulas and constants as well as a periodic table with the names of the elements and a sheet with all of the polyatomic ions. I do warn them, though, that the more familiar they are with identifying them, the more quickly they can work thorough an exam and have time to check their work.

The reason I have not required memorization is because of Bloom's Taxonomy. Remembering something is the lowest level of learning in Bloom. Ask your self this - is it more important to be able to match the phosphate ion to the correct formula and charge (Bloom - Remembering) OR to pair the phosphate ion with a metal like magnesium and produce the proper formula (Bloom - Applying)? I would argue for the latter.

One final note - after a year of applying and synthesizing all of the chemistry in General Chemistry, I am sure if I took away all of the "crutches" that my students would do just as well on the final exam.

Student Perceptions

After this discussion, I was interested to see how students felt about learning element symbols and names. I did a survey using a Google Form and several of the results were interesting.

Figure 1 (below) shows how difficult students perceived the task to be where one is "really easy" and ten is "the hardest thing I have ever done." Figure 2 shows student perception of how learning this affected their learning to write chemical formulas, which we did before Christmas break.

Lastly, while I did not format the question correctly (I'm just learning to use Google Forms), I was able to use students free-form responses to calculate how much time they spent outside of class on studying elements and names. The mean time that students spent was about 4 hours on this task over the past 5 months (September 2017 to January 2018), while the mode was 2 hours. The range was from 0.5 to 20 hours, both of which were extreme outliers.

how_hard.jpg

Figure 2

formulas.jpg