The conversion of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) into adenosine diphosphate (ADP) is an extremely important energy source for living organisms. Under common physiological conditions, it can be expressed as:

MgATP2−(aq) + H2O(l) → MgADP−(aq) + HPO42−(aq) + H+(aq)

in which MgATP2−and MgADP− represent the physiologically relevant magnesium complexes of ATP and ADP. I have found it interesting to use this reaction as an example when quantitatively discussing the Gibbs free energy.

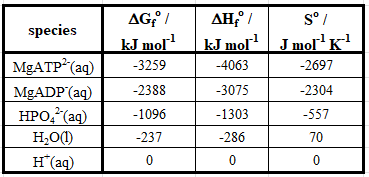

Because the reaction in Equation 1 is used as an energy source, we would expect it to have a negative value of ΔG. We can calculate the standard Gibbs free energy, ΔG°rxn, of the reaction using values of standard Gibbs free energies of formation, ΔG°f, found in the literature (Table 1).

Table 1: Thermodynamic parameters for the species in Equation 11

Does APT Provide Energy Image 1

Table 1: Thermodynamic parameters for the species in Equation 11

To do so, we use the familiar equation:

Thus, for Equation 1 we find that ΔG°rxn = +12 kJ mol-1:

Wait a minute…a positive Gibbs free energy indicates that this reaction is not spontaneous and can therefore provide no useful work to organisms. How is it that this reaction is used as an energy source for all of life on Earth?

The answer is that our calculation was done for standard conditions. However, we are interested in this reaction as it is carried out in living cells, which are not under standard conditions. Recall that standard conditions mean that all reactants and products are at 1 M concentration. So under standard conditions, [H+] = 1 M, which corresponds to pH = 0. Looking at Equation 1 and using the principle of Le Châtelier, it is seen that high concentrations of protons (on the product side) do not favor the reaction being spontaneous. However, this reaction normally occurs around pH = 7.2, corresponding to [H+] = 6 x 10-8 M. That’s a proton concentration that’s over 10 million times lower than standard conditions! So let’s run this calculation using the conditions under which it usually takes place. To do so, we’ll use the equation:

Where ΔGrxn is the Gibbs free energy for reaction 1 under physiological conditions, T is the absolute temperature, R = 8.314 J mol-1 K-1, and Q is the reaction quotient for Equation 1:

We’ll need the physiologically relevant concentrations2,3 [MgATP2-] = 3 mM, [MgADP-] = 0.03 mM, HPO42- = 5 mM, and H+ = 6 x 10-8 M. We’ll also use T = 310 K (37°C).

Insertion of all these values into Equation 3 gives:

Upon doing so, we find ΔG = -56 kJ mol-1: spontaneous, and plenty of energy for the cell to do some work!

I have found that using this example in class provides a nice example of calculating the Gibbs free energy under both standard and non-standard conditions. It also provides a nice way to discuss the principle of Le Châtelier and to integrate biological sciences into the chemistry curriculum.

References:

- Alberty, R. A. Thermodynamics of the Hydrolysis of Adenosine Triphosphate as a Function of Temperature, pH, pMg, and Ionic Strength J. Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 12324-12330.

- Tantama, M.; Martínez-François, J. R.; Mongeon, R.; Yellen, G. Imaging Energy Status in Live Cells with a Fluorescent Biosensor of the Intracellular ATP-to-ADP Ratio. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2550.

- Meyrat, A.; von Ballmoos, C. ATP Synthesis at Physiological Nucleotide Concentrations. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3070.

NGSS

Asking questions and defining problems in grades 9–12 builds from grades K–8 experiences and progresses to formulating, refining, and evaluating empirically testable questions and design problems using models and simulations.

Asking questions and defining problems in grades 9–12 builds from grades K–8 experiences and progresses to formulating, refining, and evaluating empirically testable questions and design problems using models and simulations.

questions that challenge the premise(s) of an argument, the interpretation of a data set, or the suitability of a design.

Scientific questions arise in a variety of ways. They can be driven by curiosity about the world (e.g., Why is the sky blue?). They can be inspired by a model’s or theory’s predictions or by attempts to extend or refine a model or theory (e.g., How does the particle model of matter explain the incompressibility of liquids?). Or they can result from the need to provide better solutions to a problem. For example, the question of why it is impossible to siphon water above a height of 32 feet led Evangelista Torricelli (17th-century inventor of the barometer) to his discoveries about the atmosphere and the identification of a vacuum.

Questions are also important in engineering. Engineers must be able to ask probing questions in order to define an engineering problem. For example, they may ask: What is the need or desire that underlies the problem? What are the criteria (specifications) for a successful solution? What are the constraints? Other questions arise when generating possible solutions: Will this solution meet the design criteria? Can two or more ideas be combined to produce a better solution?

Constructing explanations and designing solutions in 9–12 builds on K–8 experiences and progresses to explanations and designs that are supported by multiple and independent student-generated sources of evidence consistent with scientific ideas, principles, and theories.

Constructing explanations and designing solutions in 9–12 builds on K–8 experiences and progresses to explanations and designs that are supported by multiple and independent student-generated sources of evidence consistent with scientific ideas, principles, and theories. Construct and revise an explanation based on valid and reliable evidence obtained from a variety of sources (including students’ own investigations, models, theories, simulations, peer review) and the assumption that theories and laws that describe the natural world operate today as they did in the past and will continue to do so in the future.

Mathematical and computational thinking at the 9–12 level builds on K–8 and progresses to using algebraic thinking and analysis, a range of linear and nonlinear functions including trigonometric functions, exponentials and logarithms, and computational tools for statistical analysis to analyze, represent, and model data. Simple computational simulations are created and used based on mathematical models of basic assumptions. Use mathematical representations of phenomena to support claims.

Mathematical and computational thinking at the 9–12 level builds on K–8 and progresses to using algebraic thinking and analysis, a range of linear and nonlinear functions including trigonometric functions, exponentials and logarithms, and computational tools for statistical analysis to analyze, represent, and model data. Simple computational simulations are created and used based on mathematical models of basic assumptions. Use mathematical representations of phenomena to support claims.

Students who demonstrate understanding can construct and revise an explanation for the outcome of a simple chemical reaction based on the outermost electron states of atoms, trends in the periodic table, and knowledge of the patterns of chemical properties.

*More information about all DCI for HS-PS1 can be found at https://www.nextgenscience.org/dci-arrangement/hs-ps1-matter-and-its-interactions and further resources at https://www.nextgenscience.org.

Students who demonstrate understanding can construct and revise an explanation for the outcome of a simple chemical reaction based on the outermost electron states of atoms, trends in the periodic table, and knowledge of the patterns of chemical properties.

Assessment is limited to chemical reactions involving main group elements and combustion reactions.

Examples of chemical reactions could include the reaction of sodium and chlorine, of carbon and oxygen, or of carbon and hydrogen.

Students who demonstrate understanding can refine the design of a chemical system by specifying a change in conditions that would produce increased amounts of products at equilibrium.

*More information about all DCI for HS-PS1 can be found at https://www.nextgenscience.org/dci-arrangement/hs-ps1-matter-and-its-interactions and further resources at https://www.nextgenscience.org.

Students who demonstrate understanding can refine the design of a chemical system by specifying a change in conditions that would produce increased amounts of products at equilibrium.

Assessment is limited to specifying the change in only one variable at a time. Assessment does not include calculating equilibrium constants and concentrations.

Emphasis is on the application of Le Chatelier’s Principle and on refining designs of chemical reaction systems, including descriptions of the connection between changes made at the macroscopic level and what happens at the molecular level. Examples of designs could include different ways to increase product formation including adding reactants or removing products.

Students who demonstrate understanding can create a computational model to calculate the change in the energy of one component in a system when the change in energy of the other component(s) and energy flows in and out of the system are known.

*More information about all DCI for HS-PS3 can be found at https://www.nextgenscience.org/topic-arrangement/hsenergy.

Students who demonstrate understanding can create a computational model to calculate the change in the energy of one component in a system when the change in energy of the other component(s) and energy flows in and out of the system are known.

Assessment is limited to basic algebraic expressions or computations; to systems of two or three components; and to thermal energy, kinetic energy, and/or the energies in gravitational, magnetic, or electric fields.

Emphasis is on explaining the meaning of mathematical expressions used in the model.